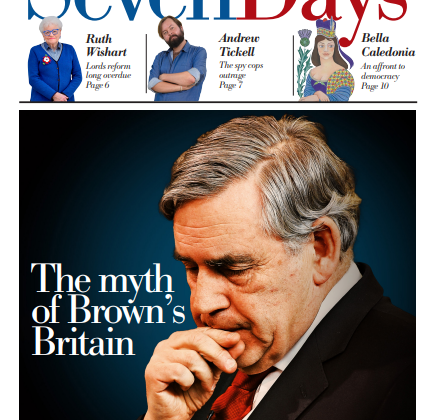

Keir Starmer, Labour and the Limits of Gordon Brown’s Britain

Gerry Hassan

Sunday National, 3 October 2021

The state of Labour matters in UK politics – and to Scotland. Can it mount a serious challenge to Boris Johnson’s Tories, or does UK politics faces the bleak prospect of perpetual Tory Governments?

Thus, the mood of Labour at its recent conference and after has consequences. The party gathering at Brighton was filled with drama, controversy – and heckling. In his lengthy keynote speech Starmer covered subjects including Scotland, the SNP, and the case for the union – citing Gordon Brown and announcing he was heading up another Labour-led initiative on the state of the constitution.

Gordon Brown remains an important figure in the party; seeing himself as a player and a contributor to, and shaper of debates, particularly in relation to the future of the UK. To this end, he has penned numerous articles and books over the years including since leaving office. Most recently his New Statesman essay two weeks ago, laying out his credo for the union, was cited approvingly by Starmer in his conference speech.

In it he claimed that the England of Marcus Rashford and Gareth Southgate presents a different, generous, multi-cultural England that challenges what he sees as the mean-spirited Tories and the Scottish nationalist caricature of England.

To this end Brown cited research from the Brown-led initiative “Our Scottish Future” which showed that 76% agreed that England’s diversity is important in making them feel proud of being English; 82% think that an equal voice regardless of race, religion or gender is important in making them proud to be English, and 83% think tolerance is important in pride in an English identity.

These figures have been used by Brown to emphasise the pluralist, tolerant character of England, with similar figures for Scotland and Wales being used to stress the pan-British consensus for progressive values. But as many observers have pointed out the above questions are close to banal, inviting near universal agreement. And the debate on the commonalities and differences across the four nations has to acknowledge that both exist – and accept in terms of the latter that the fragmented four nation politics of the present is very different from the near-homogeneous UK-wide politics of the 1950s.

Brown and the politics of division

Brown takes aim at the politics of division – “division sewn by austerity, referendums and culture wars” – lumping together uncaring Tories, Brexiteers and Scottish independence supporters, and right-wing culture warriors, all opposed by supposedly Enlightenment minded Brown.

He invokes the England of Southgate and Rashford to take aim at the politics of Scottish and Welsh nationalism – saying that the existence of this version of England “contradicts their central argument for the break-up of Britain: that we cannot be Scottish and British or Welsh and British at the same time.”

He cites the Euro 2020 football tournament held a few months ago – as well as the Olympics, and tennis sensation Emma Raducanu: “Most of us can feel comfortably at home with plural identities and found no difficulty waving the flags of St. Andrew, St. George and St David in June in support of Scottish, English and Welsh teams.”

This produced a letter to the New Statesman by Richard Haviland, from Drumnadrochit, who stated that he voted No in 2014 partly influenced by Brown’s arguments in his book My Scotland, Our Britain, but is now Yes due to Brexit. He challenged what he called Brown’s “straw men” arguments against independence: “Does he really believe that anyone’s central argument for the break-up of Britain is that we cannot be Scottish and British at the same time?”

Brown and Boris Johnson’s unionism

Reality kicks in for a bit as Brown addresses the not so rosy picture of Boris Johnson’s Tory Government – and the cumulative effect of eleven years of Tory led rule since Brown left Downing Street in May 2010. He writes that: “Attempts by some Unionists to subsume Englishness, Scottishness and Welshness in an all-consuming Britishness will not succeed.”

He offers this assessment on Johnson, the Tories and the union: “That is why Boris Johnson’s ‘muscular unionism’ simply plays into the hands of Nicola Sturgeon and her plans to provoke a constitutional crisis next year” – by which he means pursuing the politics of an independence referendum – a detail he leaves unsaid.

He concedes that Tory unionism is doing active harm to the health of the union, is denying difference and diversity, and the antithesis of a mature unionism that understood the make-up of the UK. Writing on Johnson and his government he says: “Describing the UK as ‘one nation’, he wants to badge new Scottish roads and bridges as British, as if hoisting more Union Jacks will make people decide they are only British and not also Scottish or Welsh.”

The Tories he believes are peddling a mythical, unattainable idea of power and sovereignty which invokes a UK and union which never actually ever existed – domestically and internationally. As he puts it: “muscular unionism harks back to an unrealistic view of an indivisible, unlimited sovereignty accountable to no-one but itself.”

Brexit and Scottish independence

Brown then takes a giant leap to tar the politics of Scottish nationalism and independence with Brexit and its fantasyland politics: “It is a mirror image of the Scottish nationalist playbook, for they also have a one-dimensional and absolutist us-versus-them view of the world.”

This is an utter misrepresentation and one that Brown in the 1970s and 1980s would have known as such, when he widely quoted the likes of independence thinkers such as Tom Nairn and Neil MacCormick. Posing Scottish independence as the irresponsible twin of the Brexit project is an attempt to frame it in derogatory terms, making it appear not fit for the modern world of interdependence, and drawing from the well of the disaster nationalism that gave us Brexit.

Then there is the part in Brown’s text which Starmer approvingly quoted from. Brown wrote: “When a Welsh or Scottish woman gives blood she doesn’t demand an assurance it must not go to an English patient, but instead, to whoever is most in need, wherever in the UK.” This led Starmer to say: “As Gordon Brown said recently, when a Welsh or Scottish woman gives blood, she doesn’t demand an assurance that it must not go to an English patient.”

This as many have pointed out is insensitive and inappropriate – the politicisation of blood transfusion in a debate on nationalism and independence is high stakes stuff and carries with it all sorts of connotations. It isn’t even accurate in the points it tries to make. Brown in the same speech had been lauding the four NHS systems of the UK, all organised differently; and there is a separate Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service, along with co-operation and sharing across the four nations.

Brown’s intervention brought forth a welter of letters in the following week’s New Statesman – all critical – including from former Labour MP and MSP John Home Robertson. One reader called it a “Panglossian take” based on the shaky ground that “the Labour Party will be in a position to bring about his promised new era of sweetness and light any time soon.” Another noted that Brown was trying “to squeeze life into a failed argument.”

Brown and control politics

Brown is a complex man, who in his own words is not inclined to talk about his emotions and feelings, and is for all his years in public life deeply private and conservative about opening up.

He is someone that many independence supporters viscerally dislike, often bordering on the irrational. Brown is not a bad man, but someone with many good motives who has a bad way of doing much of his politics, often bruising others, and whose diluted moral compass in office is not just a personal story, but one experienced by a generation of Labour politicians.

Michael Cockerell in his newly published study of UK Prime Ministers and senior politicians, Unmasking Our Leaders, observes of Brown close-up as PM: “I remember talking to Brown and seeing that his fingernails had been gnawed down to the quick. I felt that he was being eaten up from the inside by his years of baleful resentment against Tony Blair, and that he was eating himself up from the outside.”

According to Starmer Brown will lead a Labour Constitutional Commission set up to “settle the future of the union” which is ambitious and presumptive. It also flags the question: whatever happened to the party’s Brown led UK-wide Constitutional Convention, much trumpeted publicly in December of last year, and from which nothing has been heard? This latest venture sounds smaller, more top-down, less inclusive, and hence less likely to come up with radical recommendations which ran remake Labour’s case.

Ailsa Henderson of Edinburgh University pointed out in the aftermath of Starmer’s speech: “Labour under Starmer has shown no sense of urgency in identifying a view of constitutional change that does not turn off its former supporters or the wider Scottish electorate.”

Brown’s recent essay and other interventions glaze over much and their omissions are even more revealing. For example, where in his essay is any understanding of Brexit and the fact that as he eulogises diversity the UK is experiencing not just “taking back control” to the centre but the crushing fist of a unitary state politics being imposed on that supposedly diversifying union?

John Home Robertson replied to Brown: “Brexit Britain is itself a disruptive nationalist entity” and that “Brown’s critique of ‘narrow nationalists’ who ‘do not want to co-operate with their closest neighbours’ is in fact a disturbing critique of what Britain has become.”

Then there is the absence of a perspective – now and previously – of any sense of reflection on what New Labour and he, as one of its leading lights, failed to do in thirteen years. One key area for all the constitutional reform and devolution was remaking the political centre and aiding its democratisation. Instead Brown and Blair presided over its continued deformation from an imperial centre into a neo-liberal state.

One of the most egregious strands running through Brown’s essay is his misrepresentation of Scottish nationalism that comes from a refusal to want to understand Scottish independence. Brown has been parroting the line for years that self-government is about forcing people to choose between being Scottish and British, but no one seriously is framing the debate that way – apart from Brown.

Labour’s attachment to the ancien regime

This brings us to the future of the UK. Starmer issued the usual peroration: “We are greater as Britain than we would be apart.” Brown in his essay claimed that “the idea of a new Britain has more resonance and credibility than the talk of a new Britain in 1997.”

Yet this is frankly just warm words like the regular talk of federalism. The UK has experienced 33 years of Labour Government – which haven’t succeeded for all their achievements in fully democratising the UK, dispersing power and attacking the privilege and born to rule nature of “the conservative nation” which underpins Toryism and the forces of reaction.

Labour despite being in opposition for 29 out of the past 42 years and losing four elections in a row twice are still addicted to the mirage of capturing the ancient regime of the British state and using it to dispense goodies to the natives.

Witness this week’s Labour debate on proportional representation – supported by 83% of Labour members and 80% of local parties, but where 95% support by trade unions for First Past the Post led to the passing of a motion in support of the rotten status quo.

Labour have to break with that ancient regime, understand that the British state is a core part of the problem, British nationalism is a reactionary force, and that rather than offer to maintain this archaic feudal system they need to position themselves on the side of the forces of widespread democratisation.

That includes Scottish and Welsh self-government, Irish reunification, and addressing how England is misgoverned. To do so will require a very different Labour Party, one which will abandon the illusions which define Gordon Brown and Keir Starmer, and which even radical currents in the party might not fully embrace. But while Labour dither and delay, as the UK is buffeted from crisis to crisis, they cannot expect the rest of us to wait around much longer.