The long descent to Dominic Cummings and what comes after?

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, May 27th 2020

The story of Dominic Cummings has been everywhere in the past few days. Meanwhile the actual total of UK excess dead from COVID-19 is according to the Financial Times at a cautious figure of 64,000 and will shortly exceed the number of British citizens killed in the Second World War (67,200).

The real scandal is much more alarming than Cummings, and goes way beyond his breaking the lockdown in making a 500 mile round trip to County Durham with his wife and child. It is about the decline of British government, accountability and decency along with the rule of law.

The descent to this new low has been a long time coming with declining quality of the political classes; the collapse of cabinet government; the rise of an insider class; the conduct of special advisers and their explosion into an industry; the divisions and inequalities which deeply scar British society; and the increasing failures of UK governments to address the long-term issues of the country.

Leaving aside the ins and outs of Cummings breaking lockdown and disregard for the health and safety of others, it is illuminating to delve into the background of the man who is currently the UK Prime Minister’s most senior adviser and who is charged with being the person paid ‘to think for the Prime Minister’.

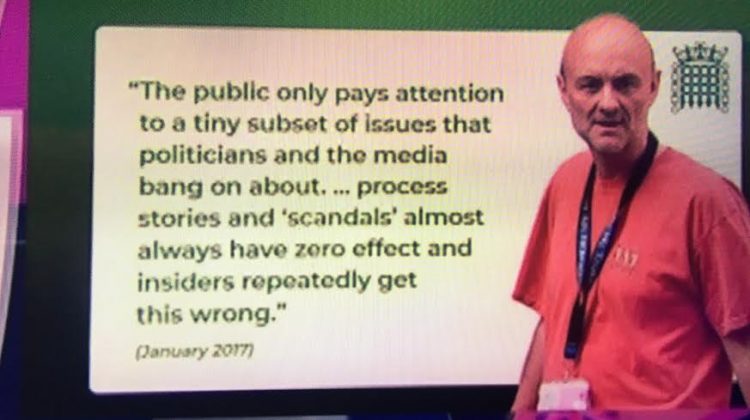

Cummings has always seen himself as a disrupter, who flouts and ignores rules and trashes tradition and processes. He has been called by friends a ‘renaissance man’ and ‘genius’, but what is clear is that he has an unbelievably high opinion of his own intelligence and does not suffer fools gladly – which in his worldview means anyone he disagrees with. He is also, despite working for numerous campaigns and currently working in No 10 Downing Street, contemptuous of organisations and bureaucracy and has a burning desire to tear things down.

Cummings first made his name in the successful campaign to block UK membership of the euro from 2000-2004. This was at a time when political elites thought that the UK joining the euro was inevitable, and in the early days of the Blair Government pre-9/11 there was a window of opportunity where public opinion was pro-European and open to the idea. Cummings put the campaign on populist terrain, forcing the pro-European camp onto the defensive, and won so emphatically that it created the groundswell for Euroscepticism to move from the issue of currency to UK membership of the EU.

He then worked briefly for the doomed Tory leadership of Iain Duncan Smith as his chief of staff where he only lasted eight months and resigned in a pique after committing such gaffes as declaring publicly that ‘The only thing less popular than the euro is the Tory Party.’ Post-Cameron entering office in 2010 he came back as Michael Gove’s special adviser at education, after being initially blocked by Andy Coulson, but by his own admission knew nothing about education, instead using it as a platform to wage war on the system from the inside.

His first experience of campaigning in a referendum was the ill-fated 2004 North East devolution vote – which saw John Prescott and Labour’s plans for limited reform emphatically defeated by 4:1, permanently killing off English devolution plans for now. Cummings, who was born and grew up in County Durham, contributed to testing the anti-establishment, anti-political class narrative which was to prove so effective in Brexit.

This was a dry run for some of the themes and styles which came to fruition in the 2016 EU referendum. ‘Take Back Control’ – those three searing words emerged in a more collegiate way as portrayed in the fictional TV account ‘Brexit: The Uncivil War’ where Cummings, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, had a eureka moment. Cummings had become a myth to friends and foes alike, but the bigger picture is that the twin pillars of the Vote Leave campaign – £350 million and Turkey joining the EU – were completely pushed by Cummings, mirroring his belief in the power of contested figures (opponents dispute them and their salience with voters rise) and his willingness to encourage xenophobic and Islamophobic sentiments in the public.

After that Cummings had to wait three years before getting the call from Boris Johnson when he became PM, then entering Downing Street as his senior adviser. When Johnson called the December 2019 election the ‘Get Brexit Done’ slogan had all the hallmarks of the Cummings school of politics – simple, memorable, populist, and with an element of impatience. Johnson and the Tories were rewarded with an 80 seat overall majority.

This provided the mandate for the UK to finally leave the EU and a window for Cummings to start dreaming of his radical agenda – remaking the civil service, destabilising the BBC and universities, and embarking on an agenda of undermining and hiving off public services. Then along came COVID-19 – just the sort of serious politics that Johnson and Cummings are temperamentally unsuited for.

Cummings has kept careful control over how much the public knows about his right-wing views. This became evident in one of the few occasions when undiluted Cummings emerged – between 2003-2005 when he set up and ran a small think tank called the New Frontiers Foundation. Cummings is ideologically against nearly all forms of public services and thinks the state should have no role in education and health. He has called the BBC the ‘moral enemy’ of the Tories, said the party should follow the US Republicans and embrace a ‘culture war’, and ‘purge the civil service and remove swathes of the top people’.

Across a host of issues Cummings has contributed with numerous others to the slow poisoning of right-wing opinion in Britain in the Tory Party and in places which used to be more careful to hide their prejudices such as the Daily Telegraph and The Spectator. In many respects this story is predominantly about the decline of the decency of English Toryism – but one Scottish and Welsh Tories have gone alone with – witness Jackson Carlaw’s twists and evasions on Dominic Cummings eventually calling on him to consider his position.

The Cummings worldview is a fantasy, representing part of the story of the collapse of mainstream conservatism into something virulent, filled with prejudice and stigmatisation, and dishonesty. It is also dangerous in that it purports to have an understanding of history, social change and innovation, based on a set of illusions about contemporary capitalism.

To take but one example, the sort of innovations Cummings has long cited as examples of rule breakers and makers of the future – the Manhattan project creating the atomic bomb, NASA putting humanity on the moon, and the creation of the internet – all of which involved the support and seed corn of the state, and in particular, the American military industrial complex. The Cummings view of the world is filled with contradictions and ignoring inconvenient facts, being fixated with militaristic thinking and systems, while at the same time yearning to destroy the state and bureaucracy.

Cummings has a propensity for quoting who he sees as great men of history such as Bismarck and Lenin. Bismarck was famously not only a great military leader but the creator of the German state and fledgling welfare state and pensions: the sort of tangible life-enhancing changes for millions that Cummings has nothing but contempt for. Lenin was leader of the Russian revolution: one of the pivotal points in the 20th century which led to the deaths of millions, yet one of the favourite quotes Cummings liked to cite is that of Lenin saying ‘There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.’

The fate of Dominic Cummings in the long run is not the big story here. It is relevant that someone with such open contempt for government and fellow human beings has been able to occupy such a central role at the heart of Downing Street. But the more important story is of something much more dangerous, pernicious and a threat to all of us.

This is the long-term decline of British government and statecraft. It was always a bit of a self-sustaining mythology but the British state and civil service in particular used to see themselves as a Rolls Royce machine – crafted, reliable, about precision. Scholars and observers of British government sold the example of it and its wisdom around the world, writing constitutions and devising systems of government post-1945 both in former colonies becoming independent such as Nigeria, Sri Lanka and Malaysia and post-war Federal Germany, with some even talking of the ‘near perfection’ of the political system here.

That confidence and insular arrogance seems a world removed now. For the decay and atrophying of British government is a long story, starting at least in the immediate period after 1945 and the survival of Britain and its institutions intact on the winning side of war giving a misplaced sense that all was well in the state of old Blighty.

This meant that through the 1950s and 1960s attempts to modernise and renew Britain and its institutions by Macmillan and Wilson were half-hearted and ultimately failed. From these failures came the hyperbole of the Thatcher revolution and its embracing of Churchillian rhetoric – ‘Putting the Great Back into Britain’ – giving sustenance to a mirage of a supposed economic miracle that was nothing of the kind but which has kept the Tory Party spellbound and entrapped since.

What the Thatcher era did do was remake the British state and government at its core, breaking up the old governing class code of checks, balances and compromises. Instead, a new insider class of entrepreneur buccaneering, self-defined masters of the universe, and think tank advocates, was born, and alongside it an industry of privatisation enablers, outsourcers and corporate capitalist apologists. This fundamental shift at the heart of government went into overdrive under New Labour and has continued under the last decade of Tory rule.

Dominic Cummings will eventually go. Boris Johnson’s time as UK Prime Minister will eventually end. But the bigger issue is what happens to British government, statecraft and the nature of the state? How are the past forty years of change to be defeated and reversed? And even more how could a remade, renewed British state which puts the care and well-being of its citizens at its heart emerge?

There is no easy road back from the debris of the last few decades. Cummings is right in one judgement he makes – that the old system of British government is broken beyond repair and the conventional establishment rules rent asunder.

What Cummings and his right-wing allies can never accept is that they are not leading lights for renewal but part of the problem and apologists for a debased economic, social and political order. Indeed as government has increasingly found it impossible or been unwilling to address deep seated structural issues people like Cummings have grown more audacious and increasingly acted as outriders for what had previously been politically impossible.

Once the controversies of the past few days subside the deformation of British government, state and statecraft which made Cummings possible will continue with or without him. The recent scandal is a wake-up call if one were needed. Putting back together a broken system cannot mean yearning to go back to the past, but taking on the new establishment, defeating them and developing a more pluralist, democratic and decentralised form of government. That will not be easy, but recent days have just underlined how rotten to the core the central organs of British government have become.