We are living in an age of multiple revolutions

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, June 22nd 2021

This Wednesday is five years exactly since the UK overall – led by England and Wales – voted for Brexit. The matter is still alive and present in so many ways – in the Northern Ireland protocol, in Scotland, in the UK argumentative relationship with the EU, and in the dividing lines which shape British politics. Here are eleven takes about the state of British politics and its future.

ONE: Brexit is not just about leaving the EU. It is not just a process, procedure and set of legal agreements. Rather it is about a wider sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo and yearning for a different kind of Britain. This is defined by its proponents as the UK as an independent country, standing on its own two feet, with less foreigners and immigrants, more monocultural and white – all wrapped up in the phrase ‘global Britain’.

TWO: This interpretation of Brexit has been embraced by Boris Johnson – particularly in the aftermath of the 2019 election victory and securing of the formal withdrawal from the EU on 31st January 2020. Brexit has become synonymous with invoking a cultural revolution that is about a Britain of ‘them’ and ‘us’ – of liberal metropolitan elites versus ordinary people, of insiders versus outsiders, of political correctness and ‘wokeness’ versus plain speaking and freedom of speech and thought. It does not matter that the new self-declared revolutionaries – Johnson, Nigel Farage, Andrew Neil – are embedded in the establishment and are insiders through and through. This is a framing device and a call to arms – knowing who your supporters are and defining your enemies as bad people.

THREE: This cultural revolution is being weaponised by the forces of the right around a host of symbolic issues – the so called ‘culture wars’, ‘cancel culture’, and totemic debates around slavery, statues and Empire. This has real connection across a host of public policies and institutions such as the National Trust for England, national museums and galleries, and universities – and is about the right challenging a centre-left and liberal interpretation of the mandate of these bodies. In so doing it is attempting to remake the public sphere and discourse, contributing to the ascendancy of a reactionary vision of England and Britain.

FOUR: Despite the calamities of Brexit and COVID – with the latter producing a modern-day disaster with 130,000 UK citizens officially dead – the UK Tories are comfortably ahead in the national polls with on average a double-digit lead. This is not some mirage – much as it causes consternation to the left – but the product of the Tories and the right placing themselves centrestage in taking about the nation and national imagination. However, this is ‘England as Britain’ – rather than a pan-UK approach (which will magnify the faultlines in the Tory coalition and crises to come).

FIVE: One factor in present day politics which aids the Tories is the rise of four nation politics – with different political dispensations in all four parts: Tory in England, SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales, and DUP versus Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland. All of this aid the Tory capture and articulation of an English politics and dimension – which sees them on current polling winning near to 50% of the popular vote in England, but even more than that displacing Labour and other opposition forces from the political conversation

This into a deep English veneration of privilege, power and belief in class that is being drawn upon by Boris Johnson and the re-emergence of private education across large sectors of life; it is a return to Victorian standards in public life with the writer Richard Tawney asking in 1931 something sadly all too relevant today – ‘Do the English really prefer to be governed by old Etonians?’

SIX: This English dimension is being fed and shaped by the forces of English nationalism – which has been amplified and given permission by Brexit – and the notion that it is more than a process or event, but about something much wider. In this there is a relationship between English and Scottish nationalism – with the two playing off of each other and gaining strength and legitimacy by standing up to the other. This has been self-evident since Scotland post-2014, of Cameron’s invoking of ‘English votes for English laws’ and the 2015 UK election where Cameron raised the spectre of SNP influence at Westminster to win back soft UKIPish votes.

The historian Colin Kidd puts it: ‘English and Scottish nationalisms are not only antagonistic but co-dependent: the rise of the SNP has provoked an English nationalist response which in turn appals Scottish opinion, and so the spiral of instability continues.’ He continues: ‘English nationalists’ pride in the prestige and idea of Great Britain is largely vacuous, ill-informed and accompanied by festering resentments of the largesse enjoyed by their fellow Britons.’ To add to this cocktail they also ‘cling possessively to British institutions, regarding them as their own – as “English in all but name.”’

SEVEN: Labour’s predicament in this is not just electoral or about its message and messenger. Rather it is existential. What has been the Labour Party message on COVID? It has been to politely disagree with the government operationally and on the optics, while leaving the big questions about crony capitalism, outsourcing and public services, and incompetence, for a latter day. Even more importantly, what does Labour stand for as Boris Johnson invokes Brexit as an all-encompassing cultural revolution? A return to quieter, calmer, more compassionate times for sure, but in the age of disputatious, noisy politics that is sadly not enough.

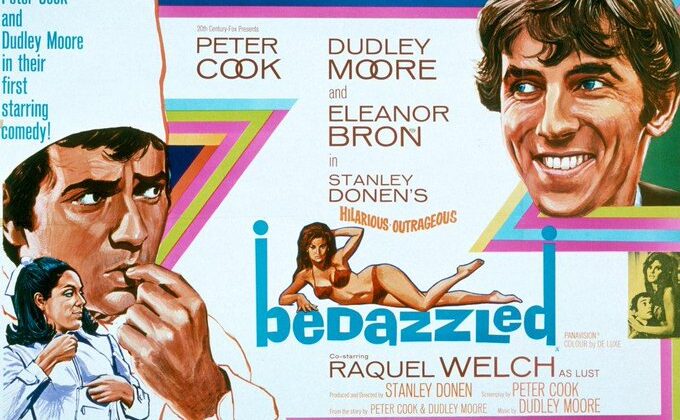

EIGHT: The forces of left and liberal opinion have to try to understand the mosaic of Tory England and voting Tory better – particularly considering the propensity of the Tories to win elections regularly. Voting Tory is not some one-dimensional act. It is not the equivalent of Dudley Moore selling his soul to the devil (Peter Cook) in the 1960s film ‘Bedazzled’ and then it all going wrong as the devil tricks him. Sometimes this is how large parts of the left view people voting Tory – which is barely adequate politically and clinging to caricature and left-wing comfort stories about political opponents.

Toryism and voting Tory is not a political sin, intrinsically evil or something which makes all its voters selfish and beyond the pale. People vote Tory for a variety of valid reasons which need to be understood including the Tories’ pitch on England; their historic distrust of government and the state and grand schemes; their championing of free enterprise, and their ability to invoke xenophobia and racist sentiments while also appearing internationalist. And critical to their success across the 20th century and early 21st century, is their unerring ability to label and stigimatise their political opponents such as Labour and the forces of socialism as ‘unBritish’.

The dominance of Toryism in recent times – winning eight of the past eleven UK elections – first under Thatcher and Major, and then in the past decade, means that this is a critical subject for non-Tories to do some thinking beyond their comfort zones. But since Cameron became PM in 2010, the hold of the Tories on office has encouraged a raging impotence in leftism and the centre-left. This is one which equates Toryism, its politicians and its voters, with being shameless, sell-outs, and a whole pile of expletives which get in the way of seriously opposing Toryism. Maybe this was always thus – but since the emergence of Thatcherism and a more ideological form of conservatism one of the main enablers in its hegemony has been the hateful left caricatures of Toryism.

NINE: Toryism in office is changing before our very eyes – shaped by the twin pulls of Brexit and COVID, and the Tory coalition created in 2019. This is disorientating for its opponents. It is no longer really accurate to describe Boris Johnson as leading a ‘hard right-wing’ government – but many still do failing to understand how Toryism is evolving and morphing into something different.

Johnson and Rishi Sunak are presiding over a significant expansion of the state, of public spending and the role of government that would have been unimaginable under Thatcherism – or in more recent times, Cameron and Osborne and their brutal austerity. The contours of British politics are being changed as a chameleon-like conservatism reinvents and adjusts itself to the spirit of the times and in so doing is wrong-footing its opponents – as Toryism has done throughout history.

TEN: This above shift is not just something happening in Britain. Instead, it is part of a momentous global shift going on – seen in the interventionist Presidency of Joe Biden, the more activist EU, and the changing politics of the G7. This is the abandonment of the last vestiges of the economic tenets of neo-liberalism – which has shaped UK and global politics for the past 40 years. Its items of faith including belief in deregulation, lower corporation and personal taxes, limited government in the economic sphere, privatisation and outsourcing, the fetishisation of finance capitalism, low inflation and the pulling back of years of social protection

The economic assumptions of neo-liberalism, withering since the 2008 banking crash have now been abandoned, but this still leaves the forces of neo-liberalism with an entrenched set of interests in finance capitalism, in the domestic states of the West and deeply embedded in public services. Adam Tooze, the global historian, thinks that as ideology ‘neo-liberalism is dead’ but that it lives on in other forms: ‘As a practice of government, neo-liberalism is a far harder beast to kill. Then if you think about neo-liberalism as a structure of social interests, as a class project, it marches on unambiguously’.

ELEVEN: This poses some big questions for the Scottish self-government debate. A Conservatism which has abandoned the tenets of Thatcherism and neo-liberalism might just have a more attractive offer for Scotland. But on the other hand it does have to smash through quite a powerful ‘tartan wall’ of how the Conservatives are perceived in Scotland, a track record which is ingrained in collective memories, and of course, Boris Johnson and the spectre of English nationalism.

More than likely most Scots will continue to see Toryism through the above prism, but it is possible that a Conservatism which continues on its present trajectory under a post-Johnson leader such as Rishi Sunak could have more traction in Scotland. It would at the minimum be a lot less toxic. That could give Toryism a small window to speak to Scotland in a different voice. But to completely change the contours of the Scottish debate Toryism has to understand that this is not just a debate about Scotland, but the nature of the UK, the British state and capitalism, and without fundamental reform of these, the self-government issue will remain a live one.

—

All of the above means that politics, government and statecraft will really matter in the next few decades. Some on the right will cling to invoking cultural revolution and within it the anger, emotion and symbols of the so called ‘culture war’. This has salience for small groups of voters, for a larger group of the commentariat, and the right-wing press, but its emergence is directly related to the bankruptcy and running out of treadmill of the economic agenda of neo-liberalism.

The world is changing in ways which would have been unimaginable pre-COVID. The state is back, government is back, and experts have a role again at the heart of government. Keynesianism has made a return from the grave. Politics is about the big questions centred on the economy, jobs, income, public services, housing and the direction of society. Fundamental crises always throw up huge change – much of it unexpected and unpredicted. The counter-revolution to the counter-revolution which has defined all of our lives, many of our choices, and the politics we have lived with since the mid-1970s has finally begun and has a decent chance of succeeding.