Gordon Jackson, Trump and the Politics of an Aging Society

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, April 1st 2020

1.

This weekend it was revealed that Gordon Jackson QC, Alex Salmond’s defence counsel, was filmed on the Edinburgh-Glasgow train talking in an indiscreet and unprofessional manner when his client’s trial was ongoing.

Jackson did not paint his client in an edifying light, stating that he was ‘a sex pest’ who was ‘a nasty person to work for’, ‘a nightmare’ and ‘bully’ as well as ‘inappropriate, [an] arsehole, [and] stupid’. Even worse than this, Jackson – a longstanding figure in the Scottish legal establishment – named two of the complainants, breaking every rule in the legal book. To save his skin Jackson, Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, has self-referred himself to the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission. If he survives with only a slap on the wrist, this will say much about the state of top legal opinion in Scotland.

Rather revealingly Jackson said at one point on the train ‘I don’t know much about senior politicians’, seeming to forget that he was a Labour MSP for eight years. He won the Labour nomination in the seat I live in, aided by Mohammed Sarwar who put his local patronage behind him. In the first Scottish elections of 1999 on polling day I took a group of international observers around the constituency to meet the candidates – and what a mixture they were: Nicola Sturgeon (SNP), Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh (Tories) and Gordon Jackson (Labour).

Jackson was convinced he was going to lose as Govan was ultra-marginal and said as much to the visitors. One asked him, ‘Why has Labour legislated for a devolved Parliament?’ to which he replied with a weary resignation, ‘You know I have often asked myself that very same question’. Strangely Jackson won the seat narrowly. Things got even more murky in 2003 when Jackson went missing during the campaign – going on a two-week holiday – and still managed to retain the seat, albeit by an even narrower majority.

During this time he was at best a part-time MSP and remained one of the most highly paid QCs in the country regularly earning around £250,000 per year in legal fees. He became known in the Scottish Parliament as ‘Crackerjack Jackson’, due to the regularity with which he would be posted absent from debates and then appear at 5pm to vote. After eight years the voters of Govan had enough and booted him out. This is the man who the Faculty of Advocates think has the judgement and character to be their most senior figure; someone undoubtedly brilliant in court and representing some of the most reprehensible characters in society, but who comes over as a total chancer.

Talking of which President Donald Trump was making a lot of noise and news this week. Trump and his administration have not been having a good coronavirus crisis – but just as the world should have been better prepared to deal with a dangerous pandemic, we had also been warned that Trump was singularly unsuited to lead in such straightened times.

Last year the writer Bryan Walsh published ‘End Times: A Brief Guide to the End of the World’, which explores asteroids, supervolcanoes, rogue robots, AI and the discovery of alien intelligence. One chapter covers ‘Twenty-First Century Plague’ and goes through Spanish flu, SARS and HIV/AIDS: all phenomena we have become reacquainted with. He turns to the risk of a pandemic and the character of Donald Trump and writes:

Trump lacks the talent and the temperament to lead the US through an outbreak … Public health is built on a foundation of trust with the public …Whatever you might of think of Donald Trump as President, it is impossible to ignore that he has acted again and again to erode trust in his own government – fighting with his own intelligence officials over Russian hacking or Saudi Arabian assassinations, censoring the science produced by his own agencies.

Walsh concludes with the prediction: ‘The consequences of these spasms of interference have been bad enough already. If the President conducts a Twitter war against government doctors during an outbreak, people will die.’ As I write Trump has been conducted his usual personal war with reality, stating half-truths and outright lies while the Republican Party, 90% of Republican voters, and organs of state go along with this as the American death total passes 3,000 – more than the totemic disasters of Pearl Harbour (2,403) and 9/11 (2,996).

Growing up in Scotland I had the distinct impression that it was dominated by a society of elderly men. They seemed to be everywhere that mattered. Politicians and public figures were nearly all old men with the odd exception; there was for example only one woman MP elected in 1979 – Labour’s Judith Hart (the year Thatcher won national office).

Then there were the grey-haired men of the Kirk and the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland which was broadcast live on TV every year. This was called by some the nearest we have to a Parliament, but it never looked like the sort of body I would want to call our Parliament or seemed very democratic. There were exceptions to this monstrous regiment of grey men and they stood out like bright stars – Margo MacDonald in the SNP and Mary Marquis on ‘BBC Reporting Scotland’ to name but two.

All this seemed to change as the 1980s progressed. Many of us, myself included, forgot about such things and assumed life had changed permanently for the better. Sometimes some of us with long memories would regale friends with tales of our dark past – which infected all society including the left – such as when Gordon Brown edited the much referenced ‘The Red Paper on Scotland’ in 1975 with 29 chapters – all by men.

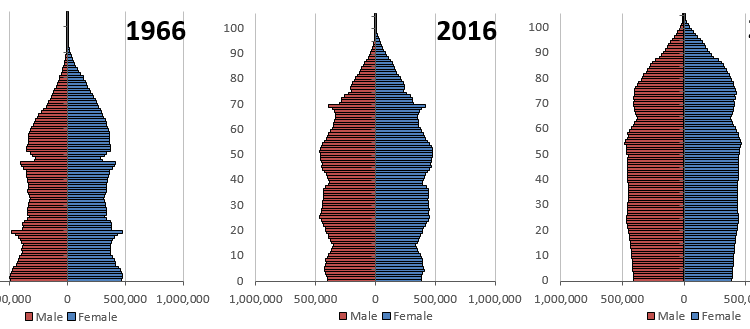

Yet the demographics of an aging society have come back to have major impact. Scotland is a more aged society than the rest of the UK; one of the underlying dynamics of the Italian coronavirus is that it is the second most aged society in the world – Japan being first.

The effects of the aging society can be seen all across the UK. One is the reverence for and importance of the NHS. Then there was Brexit – decisively voted by those aged over 65 (64:36) while those below fifty were opposed. More than that there are a host of political and public obsessions: the long-term freezing of the council tax in Scotland and England which squeezed local government to breaking point. There are the fears of middle class property owners about inheritance tax; and the contentious issue of people in England needing social care at home having to pay for it with their assets and homes which derailed Theresa May’s 2017 election campaign. And then there is the issue of over-75s and free TV licences which the BBC head Tony Hall agreed to take over from the government and is now trying to get out of.

Compare this to young people: the experience of the jobs and housing markets since the bankers’ crash; the rise of interns as entry-level opportunity in the labour market, the rise of student debt due to the astronomical student fees in England which have produced the highest student debt in the developed world; and the unsurprising fact that young people in their twenties have next to no savings – unlike older people.

Last week Max Hastings wrote a powerful piece in ‘The Times’ on what he called the problem of ‘the oldie generation’. I would not agree with all his language, but he makes a powerful case writing about the older generation:

We are the most fortunate generation in history, many of whom have shared in unparalleled history. We have been spared the obligation to fight in a war; played our part in wreaking probably irreparable damage upon the planet; known wonderful times.

He continued in the same vein:

Politically active oldies shamelessly deploy those unworthy phrases “after working hard all my life I deserve …”, or even “I didn’t fight in the war so that …” Scarcely a politician of any party dares to tell elderly voters that our good things are sustained only by heaping liabilities upon future generations.

All of this needs to be brought into the open, but where Hastings broke new ground contemporaneously was in reframing Britain’s experience of World War Two in terms of the mistakes of the elderly men of Britain’s ruling classes and of young people being called on to clean up the mess and put their lives on the line.

He provides a memorable set of quotes from Guy Gibson, hero of the legendary Dambuster raid. Gibson, who died in September 1944 on active duty at the age of 26, wrote in his autobiography, ‘Enemy Coast Ahead’ about those responsible for Britain entering the war so unprepared:

Rotten governments, the yes-men and appeasers who had been in power too long. It was the fault of everyone for voting for them. If, by any chance, we had a hope of winning this war … then in order to protect our children let the young men who had done the fighting have a say in the affairs of state.

Many of the older generation and some of their most prominent spokespeople – Joan Bakewell and Esther Rantzen; even from previous times Jack Jones and Barbara Castle in their later years, come from the best of motives and public spirit.

Yet something has gone awry in how the leading voices and collective power of the elderly is expressed. There is the understandable defensive reaction of not wanting to give up what they see as hard-won rights – free bus passes, TV licences, passing on their home to their children – although each of these, and the latter in particular, comes at huge social cost to the rest of society.

The social contract, defended by the likes of Bakewell and Rantzen, does not exist for the rest of society. It has been actively ripped up and denigrated by successive Westminster governments, and worse than that, young people have been left out in the cold. Even more damning, the prosperity and sustenance of our society is based on an unsustainable economic model, rampant individualism, and debt levels whereby young people personally and generationally are being asked again to pay for the mistakes of their elders.

The social contract which once bound us together as a society has been broken and needs to be remade. That includes thinking about how the intergenerational bonds and responsibilities are refreshed and renewed, and that has to include the older generation acting in a bit more than brazen financial self-interest.

All across society in the UK and West we have heard too much in politics, society, culture and life from the conceits of ‘the greatest generation there ever was’ and ‘the baby boomers’ going on endlessly about life in the 1960s. The coronavirus pandemic has given the opportunity and pause to say yes lets respect elders when they talk and represent wisdom, but now is a time to let younger and different voices have their say.