independence as the New Majority and the work that still needs to be done

Gerry Hassan

Sunday National, August 23rd 2020

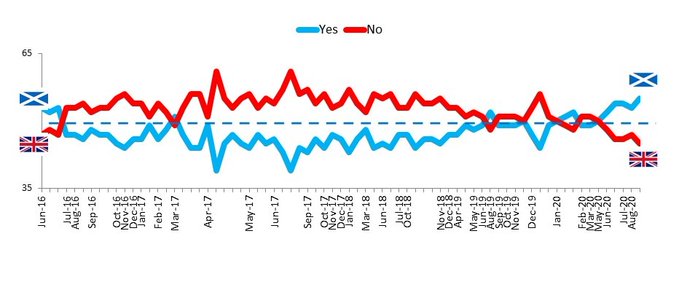

The past week has seen two milestone polls put independence in front by 55:45 and 54:46, confirming a trend over the past two months.

What is it that is moving public opinion in such decisive numbers? There is the nature of the UK, the UK Government and the rightward drift of British politics. There is the disastrous Premiership of Boris Johnson – the UK’s 20th PM from Eton, of 55 (36%) and 28th from Oxford (51%) – and an administration that seems to hold in contempt Parliament, the rule of law and independent experts. It is presiding over the human disaster of COVID-19 and alongside this the possibility of a No Deal Brexit.

The respected ‘Political Betting’ website put the situation in Scotland this week in the following terms: ‘Scötterdämmerung. The latest polling on Scottish independence really is looking like the twilight of the Union. If we exit the Single Market and Customs Union without a deal at the end of the year then I’d expect to see, post that, Yes to be at over 60% excluding don’t knows in early 2021.’

Scotland has increasingly felt like another land. There has been Nicola Sturgeon’s quiet authority and serious leadership in this crisis. The Scottish Government has made mistakes in this period, but what they have not done is undermine independent scientific and public health expertise, but put them centrestage.

Something even more deep is at work than COVID-19, Brexit and different leadership styles north and south of the border. One major factor is the normalisation of independence which has become part of the tapestry of everyday Scotland and life.

Independence has become an idea that is part of the mainstream. Even more the idea of independence has widespread attraction beyond people who will vote Yes. As a way of thinking about Scotland and our collective future it has cut through – and traction. In 2014 lots of soft No voters liked the notion of independence but stopped short of voting Yes due to detail and three main reasons: Alex Salmond, currency, and absence of the Yes camp acknowledging risk.

Politics is always about different arguments and how well people can understand their opponents to defeat them. This is a point that Kennedy and LBJ’s Secretary of State for Defence Robert McNamara made in ‘The Fog of War’ about how the US dehumanisation of the Vietnamese and a failure to understand their total commitment to victory, distorted how the Americans fought a war they could not win.

Unionism has consistently misunderstood independence. It has diminished it as hung up on flags, symbols, the past, and even those ancient shibboleths, Bannockburn, Bruce and Wallace. Ben Jackson of Oxford University puts it: ‘People who are opposed to Scottish independence think it is a nativist, ephemeral, emotional creed.’ Rather independence today is about democracy, social justice, Scotland’s future and the collective stories we make and tell ourselves, and our place in the world. Most Scots used to see all of the above as a story of Scotland in the union but today fewer and fewer do so – and it will be difficult to reverse that shift.

This is a warning to independence and the pitfalls involved in making similar mistakes about opponents. Pro-independence opinion should not fall into the trap of misunderstanding the case for the union which still has an appeal in places.

Just as it is possible to be for independence and not be a Scottish nationalist, so it is possible to be pro-union and not a unionist. There are other motivations for some such as worrying about the finances of independence, believing risk should be shared in a wider entity like the UK, fears of the disruption and uncertainty caused by independence, and for some (even though declining) an attachment to Britain and British identity.

One advantage that independence has had in recent times has been the near-absence of any attempt by pro-union politicians to understand it. Take Jackson Carlaw, Johann Lamont, or Willie Rennie. Not one has given one moment’s serious thought to the case for independence. This weakens their judgement, politics and the arguments they put forward.

A couple of weeks ago, I was speaking with a bright, politically aware pro-union supporter in their early 20s. Amid their talk of ‘Scexit’ – which I told them would never catch on as we already had a perfectly good word: independence – and reasons for Trident (jobs), they had no comprehension where the push for independence came from beyond SNP party politics. They had no grasp of recent political history and the number of Tory Governments and policies imposed on Scotland. Nor did they have any real sense of the historic nature of the independence referendum – thinking there had been a previous vote on independence in the 1970s – when the 1979 devolution vote was Scotland’s first ever standalone referendum.

The progress of independence should not shy away people from the reality that more work is needed and a new message crafted. There should be seven stories of independence.

First, the democratic case. Scotland regularly gets a UK government it did not vote for and this is a recurring situation rather than outcome of one Parliament. In the years 1970-2024, which takes us to the end of this UK Parliament, Scotland has got Tory or Tory-dominated governments for 36 of 54 years – that is 67% of the time, and nine out of fourteen general elections over two political generations.

All of our politics and how we see democracy and our collective power is diminished by our taking part as bit-players in UK elections, where the result is decided elsewhere and the UK is going in the opposite direction to a majority of Scots. This was not always the case. The 1951, 1955 and 1959 Tory governments were all elected with more votes in Scotland than Labour, with the 1970 election being the first time in post-war politics that a UK government was elected without a Scottish mandate. Now it is commonplace. Ben Jackson says of independence: ‘In the sense the argument is a democratic one … a government that is elected by Scottish voters will likely have a more left-of-centre policy profile.’ That will be up to the people of Scotland.

Second, the economic case. Scotland is the richest part of the UK outside of London and the South East. Any talk of fiscal transfers to Scotland have to be seen in the context that on official UK government figures every part of the UK has such a fiscal transfer apart from London, the South East and East of England.

Third, the social justice argument. The UK is one of the most unequal countries in the developed world and London the most unequal city in the developed world. Scotland has its own inequalities that we have to address but we are scarred by Westminster policies such as the bedroom tax, the rape clause, sanctions on the unemployed, cuts to disabled benefits and more.

Fourth, cultural change. There are two aspects to this. One is developing our own course on arts and culture free from the problematic language of ‘the creative classes’ and ‘creative industries’ which has been imported here (Creative Scotland being the obvious example). Another is the need to have a version of independence which is not just about the powers of the Parliament and politicians but includes wider cultural change. This latter point is a version of independence that the SNP have not touched in recent times: one minister telling me post-2011 that independence was about ‘extending the Scotland Act 1998 into every aspect of public life until one day we find that we are independent.’ That is an argument for independence as continuity and minimising change.

Fifth, the philosophical case. Independence has to be positioned on the centre-left while honest enough to acknowledge the limits and failures of conventional centre-left politics the world over including Scotland. We have to position independence in the slipstream of going with the social grain of the Scotland we want to see more of in the future – a future that is already here but needs nurtured and embraced: a country of individual autonomy, interconnectedness and self-determination.

Sixth, the psychological dimension. This is one of the most forgotten about, yet potent, elements in the debate. Implicit in change as all-encompassing as independence is upheaval, uncertainty and a degree of risk. These are inherent in the modern world but independence raises an element of unknown risk that is a worry to some. There is undoubtedly risk in Scotland remaining in the union: with a government presiding over a human disaster with COVID-19 and taking the UK to the prospect of a No Deal Brexit. Acknowledging risk has to be part of the independence offer, but asking who are you more confident in managing it in your interests – an elected Scottish Government or a right-wing Tory UK Government?

Seventh, the international perspective. Independence entails our country drawing on its rich talents, networks and reputation internationally – and its soft power, diaspora, cultural diplomacy and conventional diplomacy, all of which it does to an extent now but which as an independent country it can do more of. Independence involves Scotland deciding where it wants to situate itself geo-politically. We need to look 360 degrees around our shores, waters and borders – north and eastwards being a northern European nation; south to our social union and co-operation with rUK and England and Wales; to the wider European continent of our friends and neighbours; and to the broader English-speaking world of the Commonwealth of nations and beyond.

All of the above requires serious lifting that cannot be left just to the SNP leadership or the SNP. Independence as an idea is something owned collectively by everyone who wants to be part of it. That means embodying a very different version of Scotland, politics and power to the one presently on offer – where the Scottish Government acts as the main focus of political authority in the country.

If post-2021 Westminster dares to say no to a democratic mandate then they are conceding the high ground, making independence synonymous with democracy, and undermining the case for the union. A 2021 mandate is, in the words of the New Statesman’s editorial this week, ‘an unarguable mandate for a second independence referendum.’ Moreover it stated: ‘Any refusal by Westminster to grant this request (as seems likely) would merely confirm the impression that it is losing the argument.’

As George Galloway once put it in 1982 before he became in the eyes of Michael Gove the last hope of the union: ‘Scotland knows as a nation, that it did not vote for Mrs Thatcher; indeed, it very decisively rejected her …. As a nation, Scotland has both the right to self-determination and the right to decide how to exercise that right.’

There can be no standing still. But we should see part of this task as remaking Scotland as a home that looks after all its inhabitants. As Green MSP Andy Wightman said a couple of years back: ‘We are like a house that hasn’t been lived in for a long time. You go in, and you can see familiar things, but nothing really works, and you know the water needs [to be] sorted out and switched on again, and there is a lot of dust around.’

Scotland’s journey to self-government is one of continual learning, maturity and self-discovery – what Irish writer Fintan O’Toole called ‘the art of growing up’ – which will involving confronting some unpalatable truths about our society and acting upon them. But that will be up to us – and we have to learn and relearn everyday a politics and culture of taking charge of our own destiny and future.