Is This The Tipping Point of Scottish Independence?

Gerry Hassan

Sunday National, October 18th 2020

Independence is the new normal and the mainstream. This is a huge historic shift and moment. It is a dramatic change and opportunity that will require a very different politics and attitude compared to 2014.

Then independence represented the insurgents and outsiders, the new kids on the block, shaking the insiders, taking independence in from the cold and the margins. This is independence’s tipping point – or getting close to that point; the moment when everything changes: the argument, context and how the public see things with the potential to permanently alter perceptions well into the future.

This is politics for high stakes – and with it comes huge challenges for independence, the union, and institutional and public life. Up for grabs is the future of Scotland and whether it becomes independent and what kind of independence.

Independence as an idea won the 2014 referendum – something different from the detail of the official SNP offer which lost. Independence then and more so now is something that large numbers of voters find attractive and positive; this sentiment can be found across the electorate, particularly in younger voters, those under 45, and even among soft No voters. BBC Newsnight’s Lewis Goodall reflected on this observing that ‘Everytime I’ve interviewed young voters in Scotland and asked them if they’re in favour of independence, they look at me as if I’ve asked a stupid question.’

Independence as the new mainstream fundamentally changes everything and requires a different kind of independence in content and style. First, look at what is driving independence: 64% of all voters think Scotland and England are moving in very different political directions according to Ipsos MORI Scotland, while 63% do not trust the UK Government to act in Scotland’s best interests – both of which attract significant support from current No voters.

Second, as Ipsos MORI’s Emily Gray points out: ‘Boris Johnson is just toxic in Scotland’. He has 76% dissatisfaction in Scotland, while Nicola Sturgeon has 72% satisfaction rating. These two leaders and styles of leadership have been put in stark contrast by COVID-19 and define the independence debate. Johnson’s ratings are about more than the person, as Ailsa Henderson of Edinburgh University points out, with the rise of independence in part being ‘a proxy for dissatisfaction with a UK Government and UK Prime Minister’.

Third, independence cannot become identified with the inadequacies of present-day Scotland – whether health, education, local government, transport. This is a trap some SNP supporters fall into, defending every aspect of Scottish Government policy. Independence has to be about change – and not just constitutional change – but economic, social and environmental justice and greater democratisation, not just shifting power from London to Edinburgh, but within Scotland too.

Fourth, the detail of independence matters but so does the wider philosophy. Whether we can embrace maturing as a nation, facing our own strengths and weaknesses, and acknowledging where we fall short; what Fintan O’Toole called ‘the art of growing up’.

Fifth, independence involves a psychological dimension about risk, uncertainty, future unknowns and how and by who these are managed. This entails acknowledging that independence involves risk as does all fundamental change, and the central issue is who assesses these and what values informs their decisions.

Independence: An Unequal Debate

Running through all the above is the asymmetrical nature of the debate. This is a debate which understandably motivates independence supporters. Yet, it is one that many unionist supporters would rather not be having as it is not their raison d’être. Look at some of the language of unionists this week as they attempt to over-compensate.

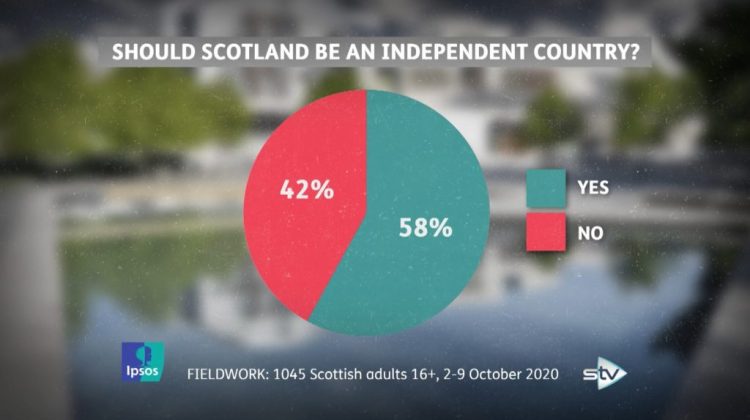

Tory MP Andrew Bowie declared: ‘The UK Government is back in Scotland. Get used to it’ which did make you wonder where it had been; John McTernan, previously Tony Blair’s Political Secretary in Downing Street reacted to the 58% support for independence stating: ‘You break it, it’s not ours to fix. Nothing to do with us’ which seemed to contain many levels of anger and displacement.

The union argument has increasingly taking shelter in detail – whether the currency, EU membership, Barnett consequentials or the economic argument. This is telling. The union case is a retreating army conceding the principle of independence and laying its last-ditch line of defence on such detail. Such a defensive politics has little chance of winning. At best it can hold out for a period.

It puts all your eggs in one basket: transactional nationalism, Barnett and the fiscal transfers across the UK. This has three weaknesses. First, it reduces the debate to the transfers across an unequal kingdom and the concentrations of wealth and power in London and the South East. Second, it is based on the maintenance of Barnett which is under attack from right-wing English Tories. What happens if a future Tory Government proposes the abolition of Barnett?

Third, the figure cited of £1,975 per head per year transfer from the UK Government to Scotland is never acknowledged in context. Scotland like the rest of the UK has suffered from ten years of Tory austerity and could lose £2,400 per head due to a No Deal Brexit according to LSE modelling. Pro-unionists cannot cite the £1,975 figure as one-way traffic without noting there is a financial cost of Scotland remaining in the union: that fiscal decisions are imposed on us without us having a say and which cause us harm.

A second dynamic is that independence has got into this place, aided by the continual misrepresentation of it by the union case. It has been associated with an over-romanticised past, with pro-Brexit historian Robert Tombs writing in The Spectator: ‘Victimhood has always been the core of nationalism’ and presenting the rise of Scottish nationalism as about Bruce, Wallace, the Declaration of Arbroath, and in more modern times ‘Thatcher, the poll tax, Tory ascendancy in England and the decline of Labour’ – and in this case the European Union. Often flags and symbols are added to this making the case that this is an irrational, emotional politics which will be defeated by rationalism.

The union argument has consistently ignored the democratic legitimacy argument of independence based on experience and principle. The former has seen 32 out of the past 50 years witness Scotland getting Tory Governments it did not vote for; this has happened two-thirds of the time since 1970 and did not happen before then; the second being the principle that Scotland has the right to decide its own future.

The evolution of the new independence

Independence has to be careful not to fall into the same argument, caricaturing all No voters as unionists or ‘Yoons’, completely ‘othering’ the British state and presenting it as a caricature which can be hard to resist with Boris `Johnson, and recognising the emotional attachment many still have to British identity and history.

The SNP are pivotal to winning independence but they cannot claim a monopoly on the project of independence. Rather independence belongs to every single person who lives in Scotland and chooses to make it their home: it is an inclusive, democratic vision.

As it becomes more popular there will be among some long-term supporters a sense of loss: the equivalent but more serious to those times when your favourite band or artist became massively popular and everyone claimed a slice of them. The Times Kenny Farquharson put this saying that ‘the Yes movement has to recognise that it won’t own independence, and won’t be able to create it in its own image. An independent Scotland will reflect all of Scotland, including the bits that didn’t vote for it.’

The SNP’s propensity to command and control politics cannot define independence. For example, a future White Paper should come from the Scottish Government but not emerge finished as a fait accompli with no warning; rather it should be owned by as wide a constituency as possible. Commentator Joyce McMillan believes that any new White Paper has to be ‘much more robust, and preferably produced by an alliance of the independence movement, rather than the SNP’ and learn from the disaster example of Brexit ‘with a majority voting for something that has never been described or properly debated.’

A pivotal issue is holding power to account, scrutiny and challenge. This is not an area in which we have traditionally done well, given how hierarchical and institutionally dominated society used to be. We cannot pose democracy here as just by default better than Westminster; rather we have to practice it, and the politics of centralisation and accumulating power led by the Scottish Government is an increasingly unedifying and unsustainable one.

The diversity and pluralism of an independent Scotland needs to be encouraged because the character of our future is being made here and now. It is worrying that, thirteen years into the SNP in office, there is still no independence supporting mainstream think tank which the Nationalists engage with and listen to – beyond the example of Common Weal. This is because the main party of independence looks with suspicion upon independent initiatives and ideas. Such an attitude has grown more pronounced the longer the SNP has been in office.

In the run-up to next year’s elections and their aftermath there has to be a new seriousness and commitment to nurturing an ecology of debate, ideas and policies beyond the control of the SNP leadership, which is part of a bigger, more open debate. Alex Bell, formerly the First Minister’s head of policy notes: ‘The challenge is as much about getting British thinking out of Scottish politics. We need a leap of imagination to solve issues about poverty, spending and the deficit.’

The alternative to this is not an attractive one – a Scotland where all the main policy ideas come from the SNP and government and the narrow insider world of corporates and lobbyists who exist in any political system and here, as elsewhere, serve their own interests.

This debate is bewildering to parts of pro-union sentiment. But not all. Some are sanguine and will be open to persuasion to come to terms with this new dispensation. Independence has to have a humility towards those not convinced. That figure of 58% is not yet permanent and includes lots of soft Yes voters as well as having the potential to rise. The Yes side has to listen to the soft Nos and ask them what do they need to hear to convince them of the merits of independence.

Finally, there is the challenge to institutional Scotland, public life and the mainstream media. The challenge to the media is an acute one: the print media has for the most part turned its back on the new Scotland emerging and dug into a unionist bunker. But the issue of the broadcasters: BBC, STV/ITV and SKY, is very different. The former in particular follows behind the curve of this debate, seemingly incredulous of the Scotland it sees before it and scared to take risks portraying and representing it. Stirling University’s Iain Docherty on the back of this week’s poll observed: ‘If independence is indeed becoming the settled will, at which point and how does the Scottish press and broadcast media pivot to recognise this?’

Scotland is changing. That carries with it huge responsibilities. Next year’s election will be a huge historic moment and opportunity for Scotland to decide its own fate and future. This opportunity belongs to all of us and we should act and recognise that we have the power to do great things which help to shape our collective future.