Looking back on the Scotland of 1979 and past visions of the future

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, 24 August 2021

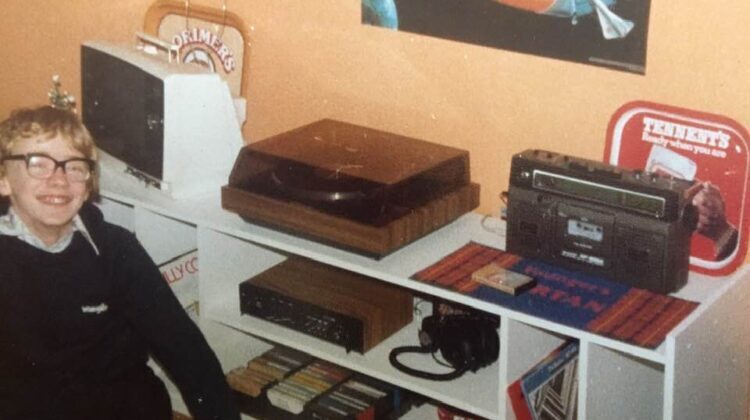

Last week I was speaking to a close friend about some of the big things in life – family, childhood, growing up, parents – and the impact all these have on who you become and how you remember and interpret the past. I recalled a photo of myself aged 15 in my home in Edzell Court, Ardler, Dundee (see above) which I had used to illustrate an article in the past year. Sitting on my bedroom floor, I was happy – with a sense of security and hopeful for myself, my parents and friends: an attitude shared by most people I knew at the time.

Aged 15, my world was shaped by love, safety, warmth and feeling protected. My parents both had jobs which while never matching their intelligence and capacity, gave them secure jobs and rising incomes, and with one exception when my dad switched jobs they never seemed to have major financial worries or anxieties. I got a profound sense from them of hope and optimism – from the personal to the political. They believed that the world was inexorably getting better, more equal and fairer – and that this was the forward march of history and the future.

All of this was in the year 1979. This turned out to be – little did I know it at the time – a watershed hinge year for Scotland, the UK and the world – the former the backdrop of Val McDermid’s new novel ‘1979’. The sense of hope and belief in the future that both myself and my parents had was, unknown to me at the time, based on the collective efforts and gains of generations of working class activism and political engagement – and was about to be dramatically reversed with huge consequences that still affect us today.

1979 saw the fall of the Callaghan Labour Government, the election of Margaret Thatcher and the beginning of eighteen years of Tory rule; the first Scottish devolution referendum; the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the start of the Second Cold War; the Iranian revolution and overthrowal of the Shah; the Sandinistas taking power in Nicaragua deposing the Somoza dictatorship; the ascendancy of the post-Mao Chinese Communist leadership and the start of sweeping market reforms; Pope John Paul II visiting Poland aiding the dramatic changes in society which were to give birth to the independent trade union Solidarnosc; and Reagan beginning his long march to the Republican Presidential nomination in 1980 where he defeated Jimmy Carter.

As a young person I had many preoccupations other than politics. 1979 was a stellar year for music – new wave, post-punk, indie, disco, soul – and I got into much of it, having a particular love of Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s ‘Rust Never Sleeps’, as well as some dodgy choices I will pass over (ELO after ‘Out of the Blue’, Supertramp’s ‘Breakfast in America’). It was also an evocative time in football and my rising passion for Dundee United.

I made my first ever visit to Hampden Park which was infamous then as a rundown dump, met my first ever National Front supporter who tried to sell me ‘Bulldog News’, and saw a boring League Cup final between Aberdeen and United end 0-0. The following Wednesday a replay ensued at Dens Park and on a memorable evening Jim McLean’s United effortlessly defeated Alex Ferguson’s Aberdeen 3-0 resulting in the first ever senior silverware for United. This was of course a harbinger for what was to come over the next decade, with both teams winning the league, challenging the ‘Old Firm’ and making their mark in Europe.

My parents were politically literate and engaged. I remember how they approached the European and Scottish referendums in the 1970s. In 1975 they voted for the UK to withdraw from the EEC, their argument being that ‘the Common Market was a capitalist club’; four years later in the 1979 devolution referendum they both voted against change, believing that Scottish self-government was not the answer.

Such attitudes were not that unusual on the left in the 1970s. Beneath both stances was a faith in Britain, and a belief that the future was about the British state making the country more equal, fairer and less shaped by inequality, barriers to opportunity and privilege. In this they drew on their own experience, born in the 1930s, and the immediate decades after the war, where the labour and trade union movement had tamed at least temporarily the excesses of capitalism.

There was also a discernible feeling with my parents that Scottishness was associated with the past, with myths, folklore, sentimentality, kitsch – all of which were seen as bad things, whereas Britain was seen as synonymous with promise, modernity and a bright future.

Their take on Scottishness drew on politics, but also had a rich cultural hinterland of references they did not like: the White Heather Club, Kenneth McKellar, Scottish country dancing, bad Scottish TV programmes, Late Call, and even the tartanry of the Bay City Rollers. They equated Scottishness with a bad relative at a Hogmanay party who they feared would embarrass and show them up in front of friends and family. There are so many layers to this: national self-loathing, not knowing your own history, working class first generation prosperity, even an element of snobbery.

There was a fissure of difference running through how my parents saw the world politically. When my father worked at NCR he was a member of the Communist Party, a shop steward and a believer in the Soviet Union. My mother on the other hand was involved in community activism, contributing to running the community centre, and helped organise rent strikes when the Heath Government forced councils to put up rents.

What I never realised as a child was that my father was mostly an armchair activist, whereas my mother lived and breathed real, everyday politics and did practical things. My father believed in abstracts: the Soviet Union, socialism, and in his latter days, Scottish independence; my mother just did things and encouraged others. This difference brought about tensions between my dad’s soft Stalinism and belief in class and my mother’s feminism; it was embodied in their different references: ‘Das Kapital’ for my dad and ‘The Female Eunuch’ for my mum. I will always remember my father’s plaintive question: ‘Why do women want a separate revolution? Why can’t they be part of the general revolution?’ He never got a reply that satisfied him; nor was he looking for one.

Living in a house filled with books during my childhood marked me out from most of my friends, and gave my life another dimension. I had decent reference books which meant from primary school my homework drew from examples and had facts. We also had a good range of high-quality fiction – with Folio Library bound volumes – and my mum at an early age introduced me to Orwell, Kafka, P.G. Wodehouse and Graham Greene. All of this was aided by being a single child – not having to share my bedroom – and with my parents having more disposable monies.

A backdrop to the above is the Scottish council housing experience which defined much of post-war society. In 1979 well over half the population in Scotland lived in council housing, including people from all backgrounds and occupations, sustained by the rising living standards of the post-1945 society. The council estate I grew up was not only well designed, having been built on what had been previously Downfield Golf Club, and hence filled with green space, woodland and play areas. It also had an incredible mix of people which I just took as given: bank managers, shop-owners, teachers and more. All of this informed the safety, security and optimism I felt, and was to be blown away by the onslaught of Thatcherism, and the selling off of council houses.

Where does all of this take us and mean in the present? Does the experience of people of my generation and subsequently throw any light on current challenges? Are there any pointers in this for younger people and the generational gridlock which so defines British society, employment and housing?

We live in a world defined by multiple crises – climate change, the leviathan of corporate capitalism, huge concentrations of power, privilege and wealth, and a politics and politicians which seems shrunken and not able to even reflect on these massive issues, let alone do something constructive. We live in a society – Scotland and the UK – that requires some profound healing, and which carries a lot of loss, bewilderment and grief in relation to COVID-19, but also in respect of other issues, where there are strident, hectoring voices who carry too much weight and attention on a host of subjects.

Since my parent’s political activism there has been a hollowing out of institutions, parties and ideas which has not helped in how we deal with the big issues. The SNP for all their self-belief have not been able to buck these trends, and independence on its own without a detailed, honest prospectus is not the sole answer.

Yet, what I also take from looking back over the past 40 years and the picture of my 15 year old self sitting is two-fold. First, the personal matters, respecting and supporting each other, and the power of trust and love. Second, that to aid such universal qualities: the political does matter and the power of the collective to do good. Somehow post-COVID and post-neoliberalism, we have to find new ways of coming together and co-operating which go beyond the allure of the abstract that my father believed in and addresses the everyday, lived democracy that my mother at her best so personified.