Scotland is back on the international stage

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, June 9th 2021

The Scottish men’s national football team are back in the finals of a major international tournament – Euro 2021 (but called Euro 2020 after the delay through COVID). This is after 23 years away, having endured ‘ten in a row’ of failed qualifications, and last appearing at any finals in the 1998 World Cup in France. The women’s team, who have attracted much attention and praise in recent years, qualified and made quite an impact in the 2019 World Cup in France.

A whole generation have only experienced the men’s team not qualifying, falling short and crushing any hopes. When this became a predictable pattern, people began to learn to dare not to hope or to dream in the first place, knowing it would only lead to disappointment and heartache. Younger football fans who don’t remember as far back as 1998 had given up on the men’s national team. Michael Grant of The Times estimated that Scotland have played 198 matches since the last World Cup game in 1998 enduring ‘a vast era of mediocrity’ which resulted in a vicious cycle of ‘poor results, lower seedings, harder qualification groups and still poorer results.’

So when on a November night last year in Belgrade, Serbia David Marshall pulled out a penalty save which saw the Scots triumph over the Serbs to reach Euro 2020, part of that younger generation experienced something close to an epiphany. They found out what it was like to be impressed by a Scotland team, and to feel connected to something bigger than all of us and about more than a mere game.

Scottish football is about more than the game

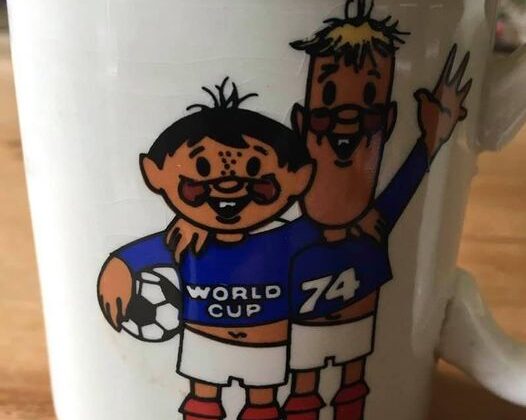

These younger fans have gone through the same mix of feelings that many of us had when Scotland broke through and made an impact in the 1970s. The experience of qualifying for the 1974 and 1978 World Cups was a watershed set of moments in how we saw football, the Scottish team – and even Scotland. This was at the same time as the country was going through an intense, divided debate about what was then called a devolved Assembly and our place in the union.

Neither the football or the politics turned out simply during that decade. Scotland experienced many highs on the football football, were unbeaten in the 1974 World Cup – the only team in the finals to do so – and then had the emotional rollercoaster of Argentina and ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’ in 1978. To cap all this Scottish voters endorsed an Assembly narrowly 52:48 which did not meet the 40% threshold of all voters (including those who did not vote), which meant it was eighteen years until Scots got another chance to establish a Parliament – decisively voting for it 74:26.

A lot of over the top rhetoric has been written about the relationship between football, politics and national identity. For example, the Argentinian debacle is often claimed as a contributory factor in the first devolution referendum going wrong. But the facts do not bear out this oft cited point. First, the SNP’s support began to decline pre-Argentina, with their failure to win the Glasgow Garscadden and Hamilton by-elections in April and May 1978. Second, ‘the winter of discontent’ of late 1978-79 eroded Labour support in Scotland as well as the rest of the UK and saw a significant rise in Tory support, including in Scotland – which increased the No vote against an Assembly.

Scotland in international finals

The Scottish men’s team have now qualified and taken part in eleven international tournaments – counting this one. Scotland qualified for the 1950 World Cup in Brazil but did not participate as the bureaucrats at the SFA made it clear that the proud Scots would only go if we won our qualifying group; we finished second to England and that was not good enough.

Then there was the 1954 and 1958 World Cups: in the former we sent a squad of thirteen players rather than 22 and lost 7-0 to the reigning World champions Uruguay. It is in this context that the success of the Scots in 1974 and 1978 in qualifying has to be seen and judged: coming after a long period in the wilderness and being Scotland’s first experience of such finals in the TV age of live matches and built-up expectations.

That was the beginning of ‘the five in a row’ World Cups where we qualified for 1974, 1978, 1982, 1986 and 1990. Subsequently we missed out on 1994 and then qualified for 1998; at the same time we first appeared in the Euros in 1992 and 1996 – contributing to a 24 year fertile period of getting to finals compared to what came before and came after. Of course it is worth noting that in all ten of these tournaments the Scottish men’s team have never progressed out of the first stage group round; the same is true of the women’s team.

The above run of finals provided a host of halcyon memories and moments. The act of qualifying for 1974 and 1978 involved epic matches against Czechoslovakia at Hampden in 1973 and 1977, and Wales at Anfield in 1977 and iconic goals from Joe Jordan and Kenny Dalglish. The 1974 World Cup did not just see Scotland return home undefeated – but we did so as the sole representatives of the United Kingdom; the latter occurring again in 1978.

1974 was the first World Cup I ever followed. My parents even marked the occasion by splashing out on a 26 inch Sharp colour TV – one of the biggest you could get at the time. For the opening match in West Germany which pitched Brazil versus Yugoslavia in our group neighbours came round for this special occasion with dining chairs set out theatre style.

Something cathartic and defining occurred with Scotland’s regular appearance at World Cups from 1974 onward. This gave Scotland visibility on the international stage when we had no Parliament or Government. This Scottish profile came to matter even more during the Thatcher decade when we qualified for every World Cup held under her Premiership.

Within this decade the reputation of Scottish and English football fans changed. Whereas in the 1970s Scottish football fans had a reputation for drunkenness and hooliganism, by the 1980s this had begun to change – one catalyst being the 1980 Scottish Cup final riot between Celtic and Rangers fans which led to the banning of alcohol at football grounds. At the same time English fans at national and club level embraced a reputation for violence and xenophobia: English teams being banned from Europe for five years after the 1985 Heysel tragedy.

‘The Tartan Army’ began to revel in a reputation for being unofficial ambassadors and cultural diplomats. This contributed to a political dimension, with Scottish fans at successive World Cups distancing themselves from the abrasive, aggressive nationalist politics of Thatcherism and the big issues of that era: the Falklands war and its jingoism, the miner’s strike and the divisive callousness of her government, and the poll tax and its imposition on Scotland one year ahead of England and Wales. ‘Tartan Army’ banners at the finals regularly referred to such causes and were widely seen and noted. This informal but deliberate Scottish opposition to Thatcher and her British nationalism has had a lasting impact on how Scotland is seen internationally.

Scottish football pioneers

Football in our country has contributed much not just to the game but society. There are the pioneering achievements of Queen’s Park – in the late 19th century the most successful football team in the world. This was the time of the ‘Scotch professors’ who invented the modern game of passing which became its form everywhere.

Scottish footballers who have made history include Andrew Watson, the first black footballer in the senior game and the first anywhere in the world to lift a trophy, who captained Queen’s Park and won the Scottish Cup in 1881, 1882 and 1886. Watson captained Scotland against England in London on 12 March 1881, when Scotland won 6-1 – still a record home defeat for England. In subsequent decades others such as Rose Reilly, who reacted to the ban on the women’s game by playing in Italy and captaining Italy to win the unofficial World Cup in 1984, have been notable trailblazers.

Football has given us great characters as managers: Matt Busby, Bill Shankly, Jock Stein, Alex Ferguson and Jim McLean to name a few. It has thrown up insightful commentators and writers who have done the game a service by capturing the elation and despair that go with being a Scottish football fan. William McIlvanney may have excelled as a fiction writer, but his football writings achieved an almost transcendental quality, particularly when trying to convey the national humiliation of Argentina in 1978. That quality of writing continues to this day of a level that should shame much of our political commentary in the success of Nutmeg put together by Ally Palmer, formerly of The Scotsman.

It is not an accident that until recently football was an arena that gave men permission to be emotional, hug and even cry. One of my most emotive moments in football with my late father Edwin came when our team Dundee United got to a European final – the UEFA Cup in 1987 played over two legs. At the second leg at Tannadice we drew 1-1 with Gothenburg and thus lost 2-1 on aggregate. As the game finished, United fans in unison acknowledged our achievement and Gothenburg’s by applauding both teams. It was a magical, sporting moment, one filled with feeling and history, and at that point in front of me my father started crying. It was the only time I ever saw him cry: they were tears for the moment as well as remembering his own father and Dundee United’s journey from the bottom of the Second Division to the top of Europe.

Football and the power of money

This brings us back to Euro 2020. Scotland are even playing two of their three group games at Hampden which must bring some small advantage. But football today is never just about the game. Rather it is also about monies and corporate interests. At a time when Glasgow City Council are savaging services and budgets, the city authorities paid UEFA £3.7 million for Glasgow to become a host city – part of a £6.2 million budget Scots paid (which is where the obligation to have the UEFA Fan Zone comes from which has become so controversial in these COVID times).

Pre-COVID, the calculation would have been that Glasgow as a host would gain millions in hospitality pumped back into the local economy: authorities having previously calculated this as £10 million. But now times are different and the city council is strapped for cash. The tourists and spending will not turn up in the same numbers, so the authorities will be left having put out significant monies for little return.

Football is always about more than football and never entirely just about money and corporate capture: the tragedy of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar notwithstanding. Euro 2020 feels significant in that it is happening after a year’s delay; for the first time the tournament is held across the continent in host cities rather than one host country – and after all these years, Scotland are back. It even allows for a little feeling of hope and optimism, given the wait has been so long.

The tournament’s pan-continental reach will illustrate the strength of anti-racism and racism, in response to Black Lives Matter, as the football writer David Goldblatt reflected: ‘European football remains a place in which racism and resistance to racism are publicly on show – and our conflicting versions of who we are – are aired.’

Scotland’s Steve Clark is a manager with the temperament and organisation to get the best out of a squad with potential. It feels like we are at the start of something. While no one would want us to replicate the excesses of pre-Argentina and ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’, we have to allow ourselves the right to dream. Who knows, after 67 years of trying we may finally make into the second round – and after that anything could happen.