Scotland’s future as an independent nation is being created in the here and now

Gerry Hassan

Sunday National, June 28th 2020

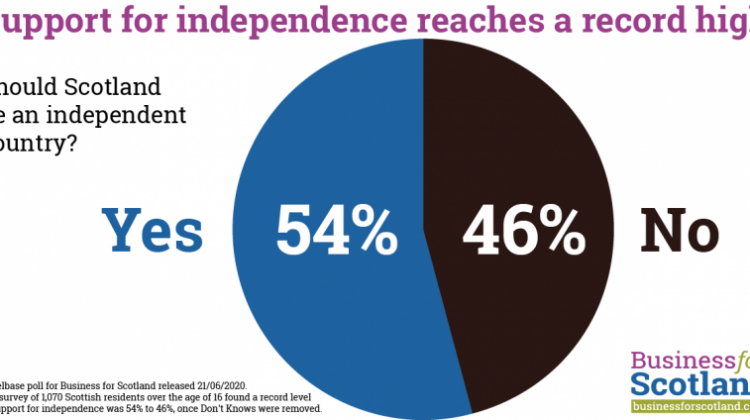

Independence is back in the news and making the news. Truth is it never went away, but last week’s 54:46 poll in this paper set a surge of energy through the Scottish political scene.

The British state and government, and Boris Johnson’s serial incompetence and inability to tell the truth in a national crisis of life and death proportions, is making the case for independence. Johnson represents all that most Scots are repulsed by – a posh entitlement Tory who thinks he was born to rule without trying too hard.

The shift to independence is aided by Johnson and Brexit but they merely magnify longer trends in Scotland namely that there is a gradient sloping towards independence – demographically, democratically, philosophically and psychologically.

Some thoughtful unionists recognise this hostile environment to their cause. Alex Massie wrote last week in the aftermath of the 54:46 poll that ‘The No vote is not just older than its Yes counterpart, it is softer too. If there were a referendum this year or next, I would expect it to be won by those advocating independence.’

Nothing is completely inevitable in politics as events and surprises can change things. Once upon a time the unionist dominance of Scotland was taken as natural and all-encompassing. But the flow of deep currents and riptides in Scotland is pushing in one direction – towards independence.

Britain as an ‘idea’ is looking beyond redemption. That means independence supporters have to get even more serious, seize the advantage, play to our strengths, understand where we still have work to do, and never complacently assume independence can just win by default.

Much concern has been understandably expressed over how another indyref comes about and indeed if it can come about. This position of thinking another vote might not be possible actually unites some pro and anti-independence support, but for opposite reasons. Paul Sweeney, former Glasgow North East Labour MP said last week in the aftermath of the 54:46 poll: ‘Why is this question still polled when a binary question will never be asked again? A Conservative Government will never agree to it.’

Let’s look at the fundamentals of an indyref and then the particulars of the case for independence. FIRST, the nature of the union is meant to be based on consent and democratic legitimacy. If a UK Government were to say NO in perpetuity this would undermine the case that is made for the union. A corollary is that 2014 has created precedent. Scotland got an indyref when there was a clear, unambiguous mandate for one; having one indyref makes having another one simpler.

SECOND, what happens if and when Westminster says NO continually entails understanding what lies underneath this thinking. Any NO does not happen in a vacuum. Rather it leads to attrition and weakening of the case for the union. NO is rather a delaying and stalling hand. It is not a position of principle or strength. Westminster is playing for time hoping something will turn up. Their weakness is evident by their lack of strategic initiatives to try to strengthen and reform the union and change the debate.

Let’s say Westminster holds out for NO for longer. This brings us to the argument that a ‘Plan B’ needs to emerge. Alternative plans and back-ups are always helpful. The question is how can Westminster’s hand be forced. Here we need to remember what an indyref is: it is the politics of process (a referendum) to progress the substance (an independent Scotland). It is the means to an end. One scenario – which isn’t a ‘Plan B’ – is that we have got to get on with building an independent country in the here and now – in institutions, attitudes and Scotland’s place on the international stage – more on which to follow.

The case for independence has to be remade and restated. SNP competence is not enough. Respect for Nicola Sturgeon as First Minister is not sufficient. And the 2014 offer is long dead.

FIRST, is the democratic argument for independence. The past 41 years of British politics have seen 28 years of Tory-led governments: that is 68% of the past four decades. That is over two-thirds of the time Scots got a government they had not voted for and explicitly rejected in emphatic numbers. That is not good or sustainable for a democracy.

SECOND, the economic rationale for independence has to be reset. This is not just about 2014 but also the limited prospectus of the SNP Growth Commission with its logic revealed by its chair Andrew Wilson when he talked of Scotland and the economic damage of COVID-19 making us as an economy ‘the worst in the developed world’. That indicates that we need dramatic change, not clinging to conventional economics.

THIRD, the notion that the current crisis means in debt, constraints and risk that independence is much less likely is wrong. This was the view put recently by The Economist. But the world is about more than money and economics. Rather it is also about trust and who you want to manage risk – a discredited Westminster class or a newly confident Scotland?

FOURTH, underpinning this are the psychological dimensions of the Scottish debate. These were critical to 2014’s outcome and will be in the future. Six years ago a majority of voters thought the uncertainty inherent in independence was just too big an ask. Now that dynamic has changed with the chaos, uncertainty and self-harm that passes as ‘the new normal’ of the UK – from COVID-19 to the prospect of a ‘No Deal Brexit’. It is no good to say – as Tory MP Tom Tugendhat did last week – of independence that it would ‘destabilise’ things and ‘leave families in trouble’; Tom obviously hasn’t had the chance to have a look at the state of the UK under his Tory Government.

FIFTH, the mishaps of the UK are not some accidental product of mistakes or bad luck. Rather they are a conscious creation of the disaster nationalism which has come to characterise the British state and politics – Tory and Labour. This mindset for all its hyperbole of ‘Global Britain’ has resulted in a UK which has turned its back on its European neighbours, has an unsure relationship with Trump’s America, and now views China hesitantly – producing a country which is unsure of its place, more insular and isolated: a shrunken, nervous, little Britain.

All of the above means we need to dig deep and recognise some hard facts. First, the SNP cannot win an indyref on their own. Second, to not just win, but win decisively, the votes of non-SNP Scotland are even more vital.

Third, the Labour Party here is critical to this and is on an upward trajectory in how its remaining supporters view independence. Last week’s poll put Labour support for independence – with don’t knows removed – at 43%: an all-time high. A majority Labour independence vote has always been one of the pillars of a decisive Yes victory.

Fourth, equally important is shoring up the Green independence vote. Last week’s poll did not have figures for what share of Green voters supported independence. A couple of years YouGov did detailed polling on the Greens and found that only 48% of their voters knew their party was pro-independence. Getting the Green vote up to a level of awareness of independence of the SNP – with similar proportions of support – could add 2-3% onto national support – which is no small thing.

Back to Labour for a moment. Even though Labour is a burnt-out wreck compared to its halcyon days it matters symbolically, in terms of trade unions, the future of social democracy and the argument for independence to the left of the SNP’s centrism.

How independence supporters engage with Labour matters. One wise counsel comes from Jim Sillars, former Labour and SNP MP, who advised SNP activists on how to deal with Labour based on his own experience in the party. He advised pre-devolution that: ‘Generalised attacks upon the Labour Party when the target should be the Parliamentary Labour Party (by far the least popular element and the most open to indictment) can too easily be taken as denigration of the whole labour movement and its history.’ This was sound advice years ago when it was made. It is even better advice now, and all the bile and hatred about Labour as ‘Red Tories’ helps nothing but the status quo.

We need to organise for the next indyref and what independence would look like now. The next campaign will be more acrimonious and contested than 2014. We will be playing for keeps and the British state know there is a good chance they will lose.

The role of broadcast media will be vital and in particular the role of the BBC. It had a terrible 2014 campaign, engaged in no proper post-mortem and has done no scenario planning on a future vote. Independence campaigners need to challenge broadcasters to treat the independence debate with the seriousness it deserves and as more than an election debate between rival parties which is how the BBC framed 2014. Rather than threaten the BBC we should be aiming to encourage them to be better: and a real BBC Scotland democratically accountable to viewers here rather than the London offshoot it currently is.

Even more we need to lift our heads from the present and set our sights on the future within our grasp. Namely we have to in our politics and activities inhabit the principles of an independent Scotland in the here and now. This means acting upon and embodying the principles and values we aspire to be now: democratic, pluralist, compassionate, holding power to account, admitting to when we fall short of our own ambitions, anti-racist, anti-sexist, outward looking and welcoming to this land of those who come to it from places which are dangerous and unstable, and profoundly internationalist.

This is not an optional extra politically. Rather it fills out the practicalities of independence and lays out the difference it can make – because in issue after issue we would come up against the limits of devolution and the unreconstructed nature of Westminster. And it addresses the terrain of the soft ‘No’ and floating voters by showing them in what ways our collective future under independence can be better.

It would have a critical undercurrent of where we at the moment are not doing as well as we should be: on issues such as redistribution, assisting those in most need, keeping the state’s powers in check over a range of areas, and empowering communities and local government beyond the centre. In short, it would begin to map out a vision of independence which was not synonymous with the current SNP’s Scotland which might be a tall ask for the Nationalists but is fundamental to winning the debate and referendum decisively and embracing and creating a different future.

Scotland has changed fundamentally. There is no going back. But to win and bring about the change that is needed to our society we have to have the confidence not only to be bold and think big, but dare to be honest, humble and have an element of self-criticism. Creating the independent Scotland of the future in the actions of the present – necessitates that we acknowledge where and when we as a nation fail to live up to the best of our values and ambitions. The campaign for Scotland’s big vote and future has already begun.