The SNP, independence and the politics of solidarity

Gerry Hassan

The National, November 30th 2020

The SNP annual conference was, like all party gatherings at the moment, a strange affair conducted through virtual discussions connecting thousands of homes and living rooms. This gave it a decent social media footprint, but restricted what broadcasters had to cover and portray to the wider nation.

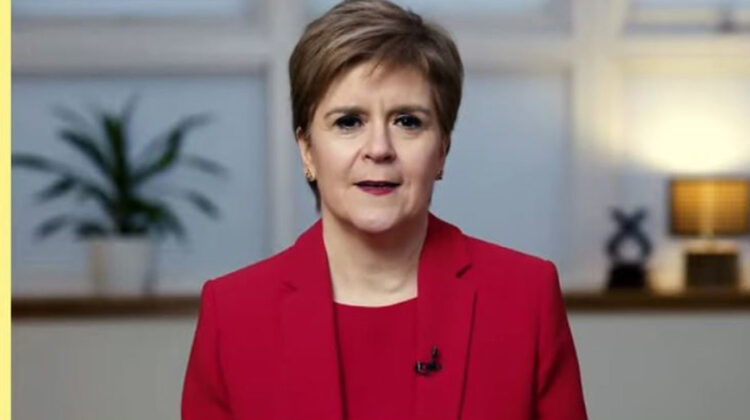

This conference was the starting gun for the 2021 elections, with the major chance for any cut through being Nicola Sturgeon’s keynote address on St. Andrew’s Day. This was carried by most broadcasters – with the right-wing blog ‘Guido Fawkes’ fuming about SKY News and others running ‘a party political broadcast on behalf of the independence campaign with SNP branding.’

There were at least three major themes running through the Sturgeon speech. First, the framing of who do you trust to decide Scotland’s future as Sturgeon expressly asked, ‘Who do you want in charge? This poses the choice between the Scottish Parliament and Government; and Westminster, ‘Boris Johnson and his band of Brexiteers’. Given the huge polling gap between Sturgeon and Johnson and Holyrood and Westminster this makes sense, positioning herself and the SNP as speaking for and defending the interests of the majority of people in Scotland.

Second, the entire speech was imbued with the language, priorities and policies of solidarity, compassion and connectedness, and in particular acknowledging the pressures – due to the COVID-19 pandemic – on children, young people and families. There were announcements of £500 towards all heath care workers, while the expansion of the government’s roll-out of a £10 weekly payment to children aged up to six to children aged up to sixteen, was cited.

Finally, there was how to address the independence question. This came in two parts, one philosophical and one political. The former part used the generous, pluralist language of the Turkish novelist Elif Shafak to embrace a world of belonging where we all have multiple identities and no single true self. This connected to her talking up the power of the Scots, invoking the agency we have as ‘decision-makers’ and ‘bridge-builders’.

In many respects this was a speech that was both a holding exercise – given COVID-19 – and a looking forward to 2021 and winning a mandate – and the potential terrain that will emerge if the SNP win that election and a majority.

In these respects, Sturgeon has to address several different audiences and constituencies, all of whom have slightly different needs and priorities. It had to reassure voters on COVID-19, the economy and society. It had to focus on the damage and hardship caused by the pandemic and offer some immediate palliatives and support. It had to re-emphasise the dividing line between the Scottish and Westminster Government, and the latter as synonymous with Boris Johnson.

On independence it had to speak to soft Yes voters – those that are part of the new independence majority – and the many who have yet to be convinced to support independence but who are open to change. At the same time it had to offer enough of a commitment and prioritisation to not disappoint those on the Yes side who are the foot soldiers and true believers, and where in places there is an element of doubt and anxiety.

That is a difficult balancing act at any time. Add to the ingredients that the above is happening in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and with the Brexit maelstrom – and the threat of a brutal, destabilising no deal at the end of the year still on the cards – it is even more challenging to pull off.

This was a decent speech in such circumstances. It struck the right tone and content. It had, as many noted, at its core a sense of heart, compassion, kindness and care for fellow Scots and human beings. That is to be welcomed compared to some of the language which comes out of Westminster politicians.

We do at some point need more. The rhetoric of talking up the power we have as voters and citizens as Scots is a positive one. The people of this nation are the agents, actors and shapers of their future – and the kind of self-government and self-determination they want. Yet, if we are to be those ‘decision makers’ and ‘bridge builders’ then we need to start seeing a different kind of architecture to our politics and society: one where we collectively create and design our own future.

This would entail a vision and idea of independence and Scotland’s future which was not just the property of the Scottish Government and the SNP, but involved a strategy of sharing power and ownership across Scottish society. That kind of prefigurative politics – shaping the kind of future, our values and priorities in the here and now – will by necessity only be possible as the contours of post-COVID-19 Scotland become clearer. It will involve risks, for the SNP to let go a bit of the grip of centralisation, and a new kind of leadership which is more open and trusting – seeing all of this as part of our collective journey and maturing as a people and nation. No one said it was easy, but the prospect of a politics which dares to do this is immense and one which even more confirms independence as our future.