Lennon at 80 and the enduring relationship of John and Paul

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, October 7th 2020

John Lennon would have been 80 this Friday. To add to the poignancy, two months later is the 40th anniversary of 8th December 1940 when Lennon was killed in front of his home, the Dakota Building, New York City, aged 40.

Lennon’s life, talent and genius are wrapped in mythology and iconic images and stories. He was central to the uniqueness of the Beatles; his partnership with Paul McCartney redefined and reset popular music and culture and, after they broke up, he embarked on a solo career which had many highs musically as well as his high-profile peace activism with Yoko Ono.

Among the many current tributes to Lennon, one stands out – ‘John Lennon at 80’, broadcast on BBC Radio 2 last weekend and still available online. The two programmes were presented by Sean Ono Lennon (John’s son with Yoko) who engaged in genuine, intimate conversations with Julian (John’s son with Cynthia, John’s first wife), Elton John and Paul McCartney.

Rare in today’s media saturated culture, we were offered a set of unvarnished, unrushed reminiscences. We heard from Elton about his boyhood love of the Beatles and first purchasing ‘Sgt. Pepper’; Paul McCartney spoke with candour on how he saw John Lennon in his area before first being introduced, noticing him because of his cool ‘Teddy Boy’ look.

The most moving exchanges were between Sean and Julian, who talked with the naturalness of brothers, despite the fact that they did not grow up in the same family, place or country: Sean growing up in New York, USA, and Julian in various homes in England and Wales.

Both are now middle-aged men – Sean, 45 this week, and Julian, 57. With all the differences between them and their distant relationship with their father – Julian seeing his father leave his mother Cynthia for Yoko at age five, while Sean had to deal with the murder of his father in 1980 at the same age – the two articulated their love and appreciation for their father while acknowledging his complexities. Even more they talked of their mutual affection and connection – with each declaring how they loved the other.

Elton gave first hand witness evidence to his role in Lennon making his last ever live in concert appearance. Elton had played on Lennon’s track ‘Whatever Gets You Through the Night’ and Elton got a promise from Lennon that if the song hit number one in the singles chart that he would appear with Elton live. The track duly topped the US singles chart and on November 28th 1974 Lennon appeared with Elton at Madison Square Garden.

Lennon played three numbers that night: his hit, ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, and most memorably, ‘I Saw Her Standing There’: a song from the first Beatles album and a song of Paul’s which John introduced by saying this is ‘a number of an old estranged fiancée of mine called Paul.’ This night was also the evening that John and Yoko got back together after a period of estrangement known as ‘the lost weekend’ (which lasted 18 months) and as a result of which Sean was born nine months later.

The McCartney conversation was one of the most genuine I have ever heard, aided by the shared love that Sean and Paul have of John. McCartney talked of the start of his friendship and musical relationship with John, and how they came to songwriting, both having started writing songs separately as teenagers before they met up. This was in an age when musicians did not write their own material – a pattern to be challenged by Buddy Holly and then torn up by the Beatles.

Paul and John’s songwriting began, McCartney revealed, even before Buddy Holly acted as a role model, and McCartney – acoustic guitar in hand – gave a rare public rendition of one of the earliest songs he wrote with John. It was called ‘Just Fun’, and had a pronounced country lilt and a certain amount of charm, as well as history, when played solo by a 78 year old McCartney.

McCartney has always been a reliable witness and mostly come over as level-headed for someone so rich, successful and lucky. He talked with tenderness of John’s relationship with his mother Julia, who died at the age of seventeen, leaving John with a lifetime fear of abandonment and which brought John and Paul closer as teenagers – Paul having lost his mother when aged fourteen.

McCartney also talked of the tensions and disagreements in the Beatles, and between John and Paul, and how it pained and upset him. He spoke openly of how glad he was that the two of them over the course of the 1970s put bitter public spats behind them, telling Sean: ‘I’m so happy that I got it back together with your dad. It really, really would have been a heartache to me if we hadn’t have reunited.’

John and Paul: A Heart Play in Music

Sean made a profound point about John and Paul’s solo work, with which I completely concur, noting that post-Beatles the music of both still seemed to be in communication, following a pattern and influencing each other: a comment validated by McCartney when he said to Sean:

The interesting thing is that ever since the Beatles broke up, and we didn’t write together, or even record together, I think each one of us referenced the others when we’re writing stuff. I often do it, I’m writing something and I go, ‘Oh, this is awful,’… and I think, what would John say? And you go, ‘Yeah, you’re right. It’s awful. You’ve got to change it.’ And so I’ll change it. And I know from reports that he did similar things to that, you know, if I’d have a record out, he’d go, ‘Oh, got to go into studio, got to try and do better than Paul.’

Sean made the comment that Paul and John’s 1970 albums – their declarations of independence at the break-up of the Beatles – had a similar feel – observing that ‘they’re both so raw and stripped down in a way and I feel they don’t sound like the Beatles in the similar way’ and that they are both ‘kind of bare’ and courageous, striking out anew.

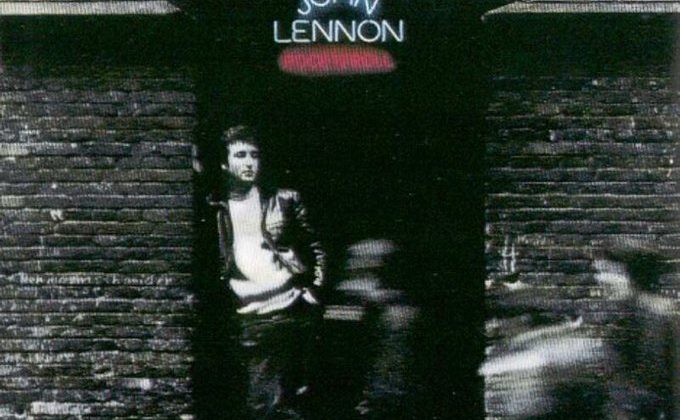

This is a fascinating insight, and all the more revelatory when you consider that on release the two albums – ‘John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band’ in December and ‘McCartney’ in April – received very different reviews. The former, his ‘primal scream’ album of catharsis and naked self-exploration in public, was greeted as genius (as was Harrison’s ‘All Things Must Pass’ released at the same time). But ‘McCartney’ with its homespun, ramshackle sound and fragments of songs (with the exception of ‘Maybe I’m Amazed’) was slaughtered by critics.

Fifty years on it is striking how over the top these divergent assessments are, and as Sean pointed out, what unites them. Indeed, I would go further and say that John and Paul’s solo work from 1970-80 was musically a kind of heart play where the two were in an emotional and even subconscious conversation influencing each other – sometimes positively and sometimes negatively.

‘McCartney’ and ‘John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band’ are both driven by a motivation to find a voice and persona post-Beatles and as individual artists. They are about emotional distress and turmoil with, as we now know McCartney’s album a product of his depression at the end of the band and uncertain about his direction. The DIY homemade sounds of this first solo album can now be appreciated as the discovery of one of rock’s greatest stars making a raw statement of anti-stardom – one which it took the music press decades to appreciate.

The John and Paul musical conversation hit the depths with the Beatles acrimony of 1970-71, with Lennon penning the vitriol of ‘How Do You Sleep?’ on the ‘Imagine’ album – the entire song an over-the-top attack on McCartney: his music, character and friends. McCartney responded months later with the heartfelt ‘Dear Friend’ on the first Wings album, ‘Wild Life’. It is one of the most emotionally honest and highly charged songs he ever wrote, a song which doesn’t back down or apologise but declares how much he loves his friend.

With the public spats behind them in 1972, in the aftermath of Sunday Bloody Sunday both released tracks declaring their solidarity with Irish republicanism and reunification. McCartney’s ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish’ was the first ever Wings single; while Lennon responded with a whole album of leftist political songs, ‘Some Time in New York City’ which is not his finest, but includes two Irish songs: ‘The Luck of the Irish’ and ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’. None of these tracks are politically and musically sophisticated.

As John and Paul’s relationship post-Beatles matured Paul even had the confidence on his critically and commercially acclaimed ‘Band on the Run’ released in late 1973 to record a track, ‘Let Me Roll It’, which was a pastiche and tribute to the sound of John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band and their reverb and tape echo with Paul singing like John.

Then came John and Paul’s musical reunion in LA on March 28th 1974 – caught on the bootleg ‘A Toot and a Snore in ‘74’ where the two of them jam chaotically on a series of old rock and roll classics such as ‘Lucille’ and ‘Stand By Me’ with a band which included Stevie Wonder and Harry Nilsson. Lennon takes vocal responsibilities while McCartney takes a step back on drums – such was the drink and drug fuelled chaos around them in this musical history: the only occasion post-1970 the two were caught on tape making music.

Lennon’s last concert appearance occurred six months later with Elton, that tribute to Paul and getting back with Yoko. At the same time Lennon’s 1974 ‘Walls and Bridges’ has in places a deep funky sound of horns, which can also be heard in McCartney’s 1975 ‘Venus and Mars’ partly recorded in New Orleans with a 1970s powerful horns sound – Lennon having agreed to play on this album and only changing his mind at the last minute.

Lennon stopped releasing music between 1975-80 to concentrate on bringing up Sean but was inspired by McCartney’s ‘Coming Up’ hit single to record the ‘Double Fantasy’ album jointly with Yoko, released less than one month before he was killed.

It shouldn’t be surprising that a musical relationship of the depth and originality of Lennon and McCartney continued long after they stopped recording together. As in all intimate relationships each aided the evolution and discovery of the other, they complemented and added to each other, and the imprint of each could be found in the way the other expressed themselves.

The Beatles shaped so much that is positive in popular music and culture to the extent that it is not much of an over-statement to divide post-war Britain into pre-Beatles and post-Beatles. They broke through the class ceiling, deference and snobbery – yet today all of those factors are still present in new, suffocating and oppressive ways.

There will be many more tributes to the wonder of John Lennon over the coming months but few will be as moving as ‘John Lennon at 80’. This was grown-up broadcasting of which we get too little nowadays; it didn’t insult the listener’s intelligence by constantly reiterating basic, well-known facts. It did not have third rate hangers-on earning an appearance fee by telling us what it was like when they first heard ‘Imagine’ or ‘Instant Karma’.

These programmes had authenticity, intimacy and honesty – and are the sort of broadcasting we need more of from the BBC. It was appropriate that John Lennon and the Beatles should inspire such quality programming: it would be edifying if, despite COVID-19 and many other challenges, broadcasters recognised that not everything has to be dumbed down particularly about subjects so precious.