Despite the lessons of history the British establishment are talking about partition

Gerry Hassan

The National, June 15th 2021

Partition has been much referenced of late concerning the state of the UK. We have seen hyper-anti-independence supporters like George Galloway float the “partitioning” of Scotland in the event of independence. And we have seen numerous Tory MPs get hot under the collar when talking about the Northern Ireland protocol, declaring that this amounts to the dismemberment and “partitioning” of the UK.

Something is clearly in the air and beyond lone political voices key figures in the British political establishment are now talking the language of “partition” with regard to Scotland and Northern Ireland. Step forward Vernon Bodganor, once seen as the foremost expert on UK constitutional politics, and the man who was David Cameron’s tutor when he was at Oxford.

One month ago, Bodganor penned a Daily Telegraph piece on Scottish independence actively promoting the idea of partitioning Scotland, if in the future the country became independent, entitled: “Could an independent Scotland remain unified?”Bogdanor is a respected scholar who likes his legal and international law references, and should know that such a move would be against all known precedents and interpretations of international law.

Not only that he dared to pose as a positive example for Scotland the case of what the British state did to Ireland in 1921-22 imposing partition and the creation of the six county Northern Ireland – writing: “The only way in which Ireland could have stayed united was, paradoxically, if it had remained part of the UK.”

Double think on partition

One month later Bogdanor is back in the same paper in a piece entitled – “We cannot stand for the partition of the UK” – the very subject he was only a few weeks previously floating as a perfectly rational response to Scottish independence. Without any great finesse he writes on the Northern Ireland protocol, which the UK Govt agreed to, signed and is now complaining about: “One hundred years ago Ireland was partitioned. The protocol in effect partitions the UK.”

Bogdanor brings a sledgehammer mindset to the Northern Ireland protocol and question, ignoring the perfidy and bad faith of the UK Government and the fact that is a crisis made in right-wing circles. One which has involved the hard clash between impossiblist Brexit fantasies and the cold light of reality. Namely that you cannot have a hard Brexit without having a hard border somewhere in relation to Ireland – either the UK-Irish border or the GB-Northern Irish border.

He comments: “The protocol transforms Northern Ireland into a condominium jointly ruled by Britain and the EU” and that given that Northern Ireland has no representation in the EU this is “no taxation without representation” – the principle which drove the American colonies to rebel against British rule.

If people think this is bad Bogdanor in his final paragraphs lets rip. He says of the EU that some of their “language is reminiscent of that of the dictators of the 1930s.” And goes on in defence of himself and the rhetoric of others: “Perhaps inflammatory rhetoric is not out of place when the unity of the kingdom is at stake.”

He should have had a look at his own writing in this piece – because he goes where no one should go – in invoking the disreputable, anti-democratic strand of Northern Irish unionism and their “no surrender” mentality in 1911-14 and 1974. So suddenly a defence of Westminster sovereignty has descended into a defence of rebellion and challenging the British state in the name of the British state.

There is so much more that is wrong-headed, inaccurate and insensitive in these two Bogdanor pieces that something more must be at play. For one the old “gentlemanly consensus” which was meant to define Westminster according to the likes of Bogdanor and Peter Hennessy: “the good chap’s theory of government” has long broken down. And with it have gone the moorings and anchor points that gave meaning to how Bodganor and Hennessy and other senior figures in what they saw as the enlightened liberal wing of the British establishment saw Britain.

One occasion in the last week of the 2014 indyref I was involved in an event with Bodganor on the subject of Scottish independence in which he was spectacularly out of touch. At one point he summarised the rising independence vote as being made of the same coalition of supporters as “the left-behind UKIP voters” – an inaccurate comment on both UKIP and Scottish independence. When I challenged him and summarised the growing constituency behind independence – including parts of the middle classes, professions and public sector, as well as those disadvantaged, he did take my point. But prior to that he had been happy to extemporise and caricature with no basis in fact.

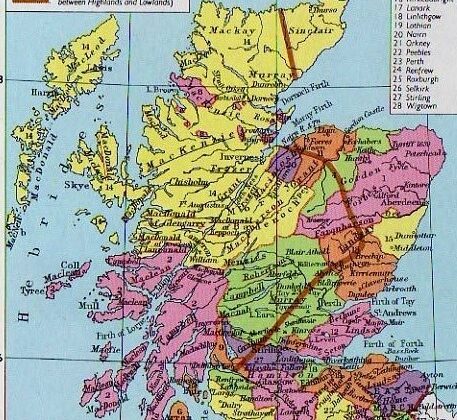

The origins of “partition” are not a happy one and remain so to this day. They are heavily associated with the retreat of the British Empire and the wanton abandonment of places by the imperial project leaving them to themselves in a mess to sort things out. Think of Ireland in 1921-22; India-Pakistan in 1947; and Israel-Palestine in 1948: all of which remain hot spots. The only other comparable examples are Cyprus (itself a former British colony) and the Cold War examples of Vietnam 1945-75 and North and South Korea (both of which were also colonial ‘possessions’ of France and Japan respectively). Thus, from the above examples “partition” is nearly always about the legacy, insensitivity and lack of any respect which is intrinsic to Empire and imperialism.

In the 2014 indyref, The Economist started to describe Scottish independence as “partition” and “the partitioning of the UK”. I explained to the editor Zanny Minton Beddoes that independence was not “partition” as there was already a legal border whose status would change in the event of independence, and that it was inaccurate in light of the examples above. The editor wrote back defending their use of the term, but for six years subsequently they have not used the word “partition” about independence once.

Vernon Bodganor, once upon a time a respected liberal voice of the establishment, should take a leaf out of The Economist’s book and stop continually using the pejorative, emotive, offensive term “partition” about Scotland and Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. He really is telling us rather more than he should: that the British establishment have lost their sense of themselves and the world and that even in its liberal circles they no longer really understand the UK – and are no longer really that liberal.