Can books really change the world?

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, 26 October 2021

The past two months has seen me spend much time packing and unpacking piles of books: putting them into boxes, labelling them, taking them out of boxes, and putting them up on newly built shelves as I recently have moved house.

It has made me think many things: firstly, about the importance of books and ideas generally; secondly, about their role and impact in my life; and thirdly, on the role of books and ideas, considering the huge challenges we face as humanity and a planet.

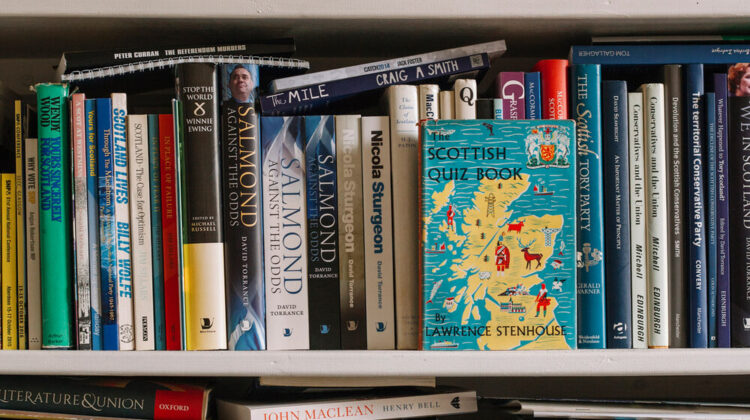

It may not surprise anyone reading this but I have a lot of books. I have been buying and collecting books for 40 years from when I was a teenager. Despite years of pruning the number of books that I have – giving away hundreds to charities and selling valuable ones – the scale and number I have has been an eye-opener. The cumulative effect of years of book buying, of keeping up with numerous debates, reading different genres, buying older books, (and yes, being a bit of completist) has slowly led to the inevitable weight of my collection.

I cannot talk about my love of books without mentioning my mother Jean who as a working class, self-taught woman loved reading and books. As a child I was very conscious that our house was a bit different, being filled with books – and in particular Folio Library volumes of a whole host of classic fiction. Thus it was my mum who introduced me to my first George Orwell (Keep the Aspidistra Flying), Franz Kafka (Metamorphosis), Graham Greene (Travels with my Aunt, Our Man in Havana), and a plethora of P.G. Wodehouse – my passion for all of the afore-mentioned has remained.

When I started buying books systematically and across numerous areas in 1980-81 it was possible to do so relatively cheaply via the wonderful world of Penguin and Pelican Books. For under a pound or for £1.99 you could buy a thoughtful book on any non-fiction subject: post-war British history; the threat of the second Cold War; psychology and psychiatry; and lots more. Most of these I purchased in the University Bookshop on Dundee’s Nethergate, where I also got into the habit of getting publisher catalogues so I could order more esoteric books on a huge range of subjects.

At this point, as a curious young man, I was trying to find out about life and the world via books, aided by receiving a Dundee University library card as part of my Sixth Year Studies at school. This opened up an Aladdin’s cave of past books, as well as specialist journals, and newly published books being profiled. I was such an avid reader that I would often read a university book on say the history of Latin America, and if I was really impressed order a copy from the bookshop so I could keep a copy to refer to again.

One missing area in my book reading at this point was Scotland, its politics and history. I read the standard textbook, James Kellas’s The Scottish Political System, which first came out in 1973 and was shaped by the onset of the 1970s devolution debates and expectation of an imminent Scottish Assembly.

By the time I read it in 1981, none of this seemed to be on the cards, and what I noted was the book’s dry, arid tone. It was written as if Kellas accepted that Scotland was a pre-democratic space run by administrators and technocrats either in Whitehall or Edinburgh, none of which seemed very exciting. This was particularly true in comparison to the febrile, dramatic nature of UK politics with Thatcherism and the challenge of Bennism and the new left in the Labour Party.

My exploration of the many facets of Scotland didn’t begin until the run-up to the 1987 election, high Thatcherism, the politics of the poll tax, through reading periodicals like Radical Scotland and recognising that even the most radical currents of the British left could be massively conservative and myopic on the politics of the UK and the British state.

Books are one way in which we define and make sense of what it is to be human. They have been pivotal to the evolution and dissemination of ideas and knowledge. And they have also been practical and theoretical tools for how we understand and do democracy and the contours of public life.

Down through the ages numerous writers and thinkers have pointed out the revolutionary potential of books; something that has also been recognised by the forces of tyranny, dictatorship and repression as they have sought to ban dangerous books, writers and ideas.

The science writer and expert Carl Sagan reflected that books are ‘proof that humans are capable of working magic’ and that:

For 99 percent of the tenure of humans on earth, nobody could read or write. The great invention had not yet been made. Except for first-hand experience, almost everything we knew was passed on by word of mouth …. Books changed all that. Books, purchasable at low cost, permit us to interrogate the past with high accuracy; to tap the wisdom of our species; to understand the point of view of others, and not just those in power; to contemplate – with the best teachers – the insights, painfully extracted from nature, of the greatest minds that ever were, drawn from the entire planet and from all of our history. They allow people long dead to talk inside our heads.

Author Neil Gaiman in a 2013 lecture ‘Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming’ for The Reading Agency (a charity to encourage children to read) said:

Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. And discontent is a good thing: people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different, if they’re discontented.

In my reading I have noticed a chasm in the world of books, ideas and the intellectual life of the West. For one, in commercial publishing there has been a diminution of the quality of many books with the rise of more celebrity based, instant, superficial publications, sometimes even on supposedly serious subjects. At the opposite end, much academic publishing has become so particular and concentrating on the minutiae that it has little if any real impact or purpose.

Even more importantly for all of us I have over the years felt in my reading a profound, growing collective failure to respond adequately and understand, analyse and proscribe solutions for the challenges of the age.

I think this is true – from the environmental and climate crisis; to the pressures and constraints on democracy, political engagement and government; the concentration of power and privilege; the forward encroachment of technology, information and surveillance capitalism; and a global order which has increasingly resembled a world of power politics.

I have read many good books in these areas. On climate change and globalisation: Richard Eckersley’s Well and Good: How We Feel and Why It Matters changed my view of the latter, with its connection between ‘the official future’ of the latter with the self-esteem of young people in Australia; Colin Crouch’s Post-Democracy outlined the challenge of the new elites; and Naomi Klein’s No Logo. On Scotland and the nature of the UK Tom Nairn’s The Break-Up of Britain altered how I saw the UK and understood nationalism, while Neal Ascherson’s Games with Shadows gave a more impressionistic account of the slow fragmentation of the UK.

Books of course are merely one means by which ideas, exchange and public discourse occurs, but surveying my adult lifetime of reading I worry about whether we are really able to be serious and confront the scale of problems which currently besets humanity.

As we approach Glasgow and COP26 we have to get serious about climate change which necessitates opposing the notion of endless growth and economic determinism: a fetish which is found as much on parts of the left and right; we need to forensically map out and comprehend the grotesque levels of wealth and privilege and not let the ultra-elite think it appropriate to see their future as separate from the rest of us; alongside there is the weakening of democratic institutions, values and agents of change; and as well as all this we face the rise of high tech, algorithms having power over us, and the march of AI and automation.

That seems a tall order for humanity to get its head round, and for us to be able to have common conversations that have connections and a willingness to take action. The human race has in previous ages managed to rise to major challenges – whether eradicating many killer diseases, defeating the forces of Nazism and fascism in World War Two, or managing in the first and second Cold Wars to not annihilate the human race.

To ensure this planet remains habitable for humanity and the millions of species which live here we have to nurture a culture both of ideas and agency, and to believe that we have the collective capacity to bring about positive change. Books in the past have been one key platform in this and it would be uplifting to hope that in an age of information overload they still have a major role in how we decide and try to shape our future.