How the 1970s began for me and how I was nearly written off at the age of five

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, 22 June 2022

It did not start too well for me: the seventies.

I was only a few months into primary school. Making friends. Finding my feet as a shy, sensitive only child used to being the centre of attention of my parents.

I had many advantages. The school I attended had been built and opened to mark the completion of the new expansive council estate that I lived in on the outskirts of Dundee. It was filled with green spaces, woods and places for kids to have safe fun and use their imagination – all of which were to play a major part in my years growing up.

Another was that the primary I attended was a mere couple of minutes from my front door. Even more that route was a simple A-B down a gentle gradient. This meant that from a very early age, indulged by my mother, I would put off getting up until the last minute possible – by 8.45 – have a quick breakfast and be in school by 9. All accomplished despite living on the thirteen floor of a tower block. It was that easy.

I remember my first day at school. Being taken by my mum to the school hall and waiting for my name to be called out. I can recall the nervousness then and of the night before. I can still sense my surprise on the second day when my mum indicated that rather than take me down to the school gate herself that I should go on my own. I was scared but it all turned out fine.

None of these moments prepared me for what turned out to be a watershed occasion in my life. One I did not comprehend as such being a mere five and a half years old at the time.

Here I was in a room with two of my school mates, Derek and Geoff, along with Miss Paterson – deputy headmistress, who had a fearsome rod of discipline running through her. She had a face which fascinated me from the moment I saw it, filled with striking, deep lines marking her years and character.

As well as her there was also a remedial teacher whose name is now lost in the mists of time. She seemed in charge of our educational prospects and the general air of that day was one of resignation and that not much could be done or expected from myself, Derek or Geoff.

I did not really understand much of what was going on, what things like ‘prospects’ and ‘intelligence’ were. The remedial teacher said words that seemed to have a great deal of import telling us: ‘I am afraid your presence in the normal class is disruptive and not helpful for you or the rest of the class. So, for now on you will be all be given special treatment.’

‘Special treatment’ to me usually meant sweets or getting to stay up past my usual bedtime, but somehow this did not give the impression of being a treat.

The shape of the room and its layout are etched in my memory, and seemed to be of vast proportions with Miss Paterson sitting as far away from us as possible. And I can visualise lots of the detail. The dark wooden colour of the tables; the seemingly circular nature of the room and table. I can see myself in that room sitting at one end alongside Derek and Geoff, with Miss Paterson and the remedial teacher at the other. The three of us feeling utterly helpless; the two adults with power.

We were just over five years old. Our lives had been decided for us by the school authorities. This was it. This was as far as it went for the three of us in terms of life opportunities. We had been given no say, no real discussion or warning, and our parents were not presented with any alternatives. It really was that crushing and final. And to add to all this, neither myself, Derek or Geoff, really had a clue what was going on or what had been decided. We were that powerless.

Cut to a meeting a day or two earlier. Miss Paterson met with my mother Jean. It seems I was having serious trouble in class. I cannot keep up with lessons. Miss Paterson tells my mum that the situation is grim and beyond hope. She says in the most forthright terms in words that my mum never ever forgot: ‘Mrs Hassan, Gerrard is sadly never going to amount to anything. Have you ever thought about having another child?’

These words were like a red rag to a bull. They were an affront, insult and challenge to my mum. And ones she was determined to prove completely and utterly wrong.

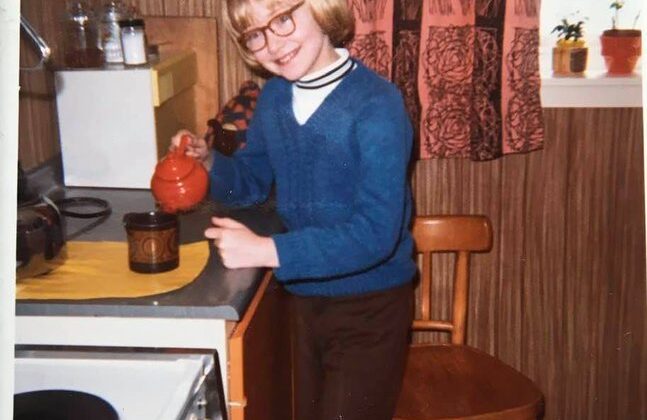

Fast forward a few months into the summer of 1970. The perseverance of my mother came to the fore. She pushed and pushed. I went for exhaustive eye tests. No one at the school had bothered to consider that I might be having trouble with my eyesight.

I went to Dundee Royal Infirmary and met with specialists who gave me all sorts of examinations. I went to opticians who asked me to wear a patch over my left ‘good’ eye when watching children’s TV every night immediately after school. Eventually after several months of testing and expert advice the solution came forth that I needed specs because I had a ‘lazy’ right eye.

Specs were not the greatest news for a now six-year-old already self-conscious, who had already been singled out as being ‘not very bright’ and practically thrown on the scrapheap.

Once I got my specs I could see properly and understand and contribute to lessons. It still felt uncomfortable wearing them with other pupils making numerous derogatory terms about them it seemed all the time.

Once this ritual was established I used to deliberately forget them. I would go to school and declare spec-free that ‘I no longer needed to wear them’ only to be followed by my mother half an hour later. She would enter the classroom and hand the specs to me in front of everyone. This became a bit of a minor ritual until I gave up resisting.

Wearing them was clearly better than not wearing them. I was not in a remedial class. I was no longer picked out by teachers for ‘special treatment’. And I actually began to enjoy and even thrive at school.

Derek and Geoff had very different experiences. They remained in our main class but with extra support. They were seen as ‘rough boys’ by teachers. We all became friends although never once referred to that experience which united us. We were little boys who had our lives decided by others.

One of our early teachers, Miss Holroyd, said to me: ‘I have no idea why you and Derek are friends. You have nothing in common.’ A strange way to speak to a six-year-old. And yet she should have known. We had an unspoken pact, joined together at the hip by the authorities and their decision to give up on us.

That was the start of the decade for me; so dramatic and life-affirming that at the time I had no comprehension how my mum and her stubborn character and willingness to challenge authority had changed everything for me.

This story became one of the narratives of my life, told and retold by my mother down the years. I grew more and more to grasp the thin line between being a success and being encouraged and written off.

It did not work out for Derek and Geoff in terms of education and life chances, and Derek in particular was a troubled child. He tragically killed himself at the age of eighteen in the early 1980s, jumping off the Tay Road Bridge. His mum said to the local media at the time: ‘ In the last weeks of his life he saw Charlie Nicholas and the Pope’ as if that was some kind of consolation for the tragedy and waste of a life.

Neither myself or my mother ever got an apology from the school. Years later when I won a range of secondary school prizes in Sixth Year my mum wrote pointedly to the primary school, reminding them of their arbitrary decision and writing me off at such an early age. She never even got the decency of a reply.

I often think of Derek and Geoff and that day. I owe so much to my mum. She had her faults like everyone, but she stood her ground and challenged authority which thought it knew best. She always did. And she singlehandedly changed my life.

That was the start of the decade that was the 1970s for me. From now on it was going to get better.