The British Empire is still very much alive and kicking

Gerry Hassan

Scottish Review, September 23rd 2020

The British Empire has never really gone away. Its presence and influence has always been here – sometimes in the background, often in the foreground, being invoked, defended and even celebrated by some.

It is there in the ridiculous debates about the UK ‘punching above its weight’ on the global stage, the painful dependency of UK elites on ‘the special relationship’ with Washington, and all the clinging to the wreckage of the UK’s diminished international status and that’s without mentioning Brexit.

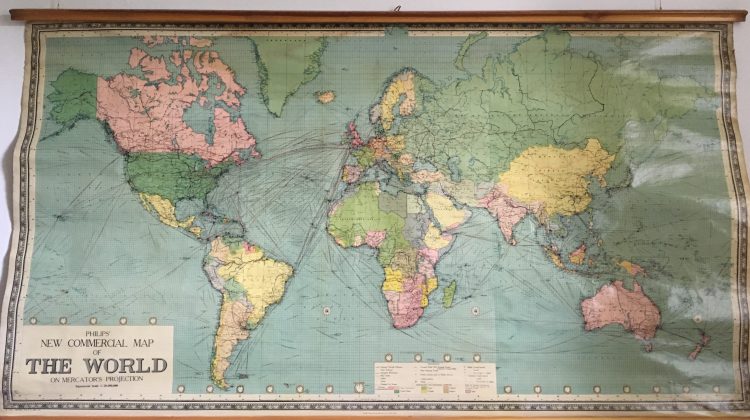

Like many fascinated by British history, I have always been interested in the rise, fall and legacy of the British Empire, and tried to comprehend the subtleties, nuances and stories of it beyond simplistic narratives. In recent years I have wanted to buy an original map of the British Empire at or near to its peak. In the last few months of the 2014 indyref I spoke to a couple of antiquarian map dealers in Charing Cross in London. I explained to one that my search was not pro or anti-Empire, but that this endeavour had existed and defined a lot of what Britain and Britishness was. One told me that such maps – usually school maps – were very difficult to get hold of as they were topped and tailed by wooden straps and these tended to stretch and break.

Fast forward to two weeks ago. I was on a trip to Glasgow Salvage in Paisley, run by Scott and Stuart. Their yard is a treasure trove of interesting objects and forgotten local history such as advertising signs and newspaper billboards for old football matches. Stuart showed me a map of what was ‘British India’ pre-independence and I asked more in hope if he had any maps of the British Empire.

He then unfurled a huge map of the entire world from 1958 – and the British Empire just as it was embarking on systematic decolonisation. Thus India and Pakistan have become independent; Palestine has become the state of Israel in its pre-1967 borders; Egypt has gone from a ‘protectorate’ to independent, while most of Britain’s African colonies remain at this point under the control of the Empire.

1958 does not seem that long ago in many respects. It represents the world before I was born but still seems of recent vintage and part of the modern world. 1956 witnessed the British and French invasion of the Suez Canal in Egypt in collaboration with Israel. This saw the UK humiliated internationally with the UK Prime Minister Anthony Eden caught lying to the Commons and forced to resign; while the weakness of UK economic power was revealed by the pressure the US were prepared to put on the UK to force us to withdraw.

The same year Khrushchev made his legendary speech denouncing Stalin’s ‘cult of personality’ while the Soviets invaded Hungary; the following year the European Economic Community was born (without the UK joining) and the space age began with the Soviet successful launch of Sputnik into orbit.

If it seems nearby in some respects in others it is a far-off distant world. At one margin of my map – which when I got it home was even more magnificent and in surprisingly good condition – is a guide to the European ‘colonial powers’ – the UK, France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium and the Netherlands. And there in their non-glory are such entities as ‘French West Africa’, ‘French Equatorial Africa’ and the shadow of the infamous ‘Belgian Congo’.

The last conventional decolonisations of the British Empire were the emergence of Zimbabwe in 1979-80 and Belize in 1981; while the motley crew of British Overseas Territories from the Falkland Islands to the Cayman Islands and Bermuda are remnants of Empire (more on which below). Spain run by the Franco dictatorship until 1975 relinquished Equatorial Guinea in 1968; while Portugal – a fascist dictatorship until the ‘Carnation Revolution’ of 1974 – only decolonised in 1974-75 resulting in bitter struggles on Angola and Mozambique.

Such maps formed a backdrop to the lives of so many of us and stayed up on classroom walls when Empire was supposedly a thing of the past. I have a distinct memory of such a map being on the wall at Ardler Primary in Dundee until at least 1975, and remember it vividly. For one, I was fascinated by maps, geographies and topographies, and was very curious about the political and administrative changes which dated maps and made current maps historical. I remember Ceylon becoming Sri Lanka, East Pakistan emerging as Bangladesh, and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and subsequent division of the island – the last of which I tidily coloured in on my map of Europe.

The British Empire map of my childhood was just there. Uncommented upon as out of time and place. The UK was supposedly a post-imperial country having put things like Empire behind it and embraced Europe. My childhood was filled with a distinctively subversive mainstream culture where John Cleese would say ‘Don’t mention the war’ in an episode of ‘Fawlty Towers’ and those of us growing up with grandparents who were defined by it but usually never mentioned it, knew what this meant. Yet that map sat there and even as a child I knew there was something wrong. It felt so natural. And yet it also felt incongruous: why was it still there undiscussed and clearly viewed as the present rather than a relic of history?

I was not alone in this experience. After purchasing my map, a photo I posted on social media led to a host of reminiscences from people who remembered similar maps well into the 1970s. Colin Haggerty said ‘I remember this map from Abercorn [Primary] School in Paisley’, and Claire McNab pointed out that administratively ‘the British Empire didn’t formally disappear under 1 January 1983 when the remaining colonies became rebranded as ‘British Dependent Territories’, then ‘British Overseas Territories’’: due to the British Nationality Act 1981. She concluded, ‘So, ironically, it was Margaret Thatcher who formally abolished the British Empire’ although she never left it as a mindset.

James Mitchell of Edinburgh University reflected that: ‘The worldview of the generation who taught in schools in the 1960s and 70s was formed much earlier, in the days of ‘Great’ Britain, WW2 and Empire casting long shadows. This was the world they in turn transported into classrooms and young minds illustrated by the Empire map.’ He thinks maps such as my empire map have an enduring influence: ‘The current context is only one influence. The texts used in teacher training, in classrooms of our teachers are important. That map is more than an historical artefact, it suggests a hankering for a ‘better yesterday’’.

These maps hung on walls as Labour and Tory Governments administered what became ‘the post-war consensus’ and remained as it began to fray, decay and fracture. By the mid-1970s the UK had seen Ted Heath, Harold Wilson and then James Callaghan struggle with issues of relative economic decline, public spending, the influence of trade unions, and often unstated but lurking behind it, the failures of British capitalism.

All of this reached a crescendo in 1976 when Callaghan went to the IMF for a loan to bail the UK out, major public spending cuts came about, and critically, Callaghan in his keynote Labour conference speech embraced monetarism, chastising an unconvinced party that ‘We used to think we could spend our way out of recession’. This was the beginning of the retreat of social democracy in Britain – one it has never fully recovered from – and the ascendancy of Thatcherism.

Looking back on the long shadow of Empire it now appears clear that the window and opportunity to reform and democratise the UK was a relatively brief one. The great enduring achievements of the Attlee Government were built on the back of the warfare state, literally, with Labour’s five years of coalition from 1940-45 with Churchill and the extension of the state and planning powers continued post-1945. But more important in the longer-term Attlee and his ministers were ardent centralisers and believed in the power of the state to bring progress, enlightenment and redistribution. Hence, they tried to build their bright, new social democratic ‘Jerusalem’ on top of the edifice of what was an Empire State: a state built not for the well-being of its citizens, but military conflict and conquest and the running and maintenance of an Empire.

By the 1970s the fissures and tensions in this worldview had come into full view, and a counter-revolution was beginning on the right which coalesced into Thatcherism and on the left associated with Bennism which nearly converted the Labour Party. Thatcherism was many things and complex and contradictory in office. Yet as an ideology it spoke to a vision of Britain and its place in the world which drew from the imperial mindset and imagination of the Empire at its peak, and illusions of British grandeur in the past from ‘Victorian values’ to the veneration of a mythical Winston Churchill and his leadership during World War Two. All of this morphed as the 1980s went on into a triumphalism with such overblown rhetoric as ‘we put the great back in Britain’ – which now has a Trumpian ring to it.

The point being that the Conservative Party aided by Labour timidity failed to make the UK a modern, post-imperial, European country. Instead of embracing a future about the well-being, education and life chances of its citizens, politics and government under Thatcher, Blair and Johnson embraced a hyper-blown language of being the best in the world – as seen in the ‘world beating’ track and trace system which still isn’t working.

The map of the British Empire on my school wall was a sign that something was wrong. It was a mixture of not letting go and denial. It showed an unwillingness to confront who we were and are and what had been done in our name. Some wanted to remain in an empire of the mind perpetually; others thought it was all a harmless irrelevance now in the past which would remain there as we did the things normal countries did such as build a fairer society.

The map was a living embodiment of the Empire State, and has influenced the past 40 years in giving us a politics shaped by British exceptionalism and fantasyland notions of greatness and uniqueness. It had led us to think that we can still ‘punch above our weight’; act as great counsel to the Americans; and in the ultimate calamity of Brexit sail off back into the sunset and reclaim our imperial legacy as swashbuckling, buccaneering, dare devil capitalists.

If somehow people still think this delusional belief in grandeur does not really matter here is Boris Johnson, the UK Prime Minister, offering an explanation this week on the disastrous record of the UK on COVID-19 in comparison to our European neighbours: ‘There is an important difference between our country and many other countries around the world. And that is our country is a freedom-loving country, Mr. Speaker. And if you look at the history of this country over the last 300 years virtually every advance from free speech to democracy has come from this country.’ All offered as a cover for the UK Government’s mix of bumbling amateurism and corporate give-aways to its pals.

Maps on walls matter and the British political imagination has tragically become a prisoner of those out of date maps of imperial conquest and power. The Empire truly did strike back.