What are we talking about when we talk about Thatcherism?

Gerry Hassan

The National, August 10th 2021

Boris Johnson was at it last week. Upon visiting Scotland he was yet again causing mischief and being offensive, becoming the story in a way which did not do him any favours, nor the cause of the Tory Party and union, or indeed, the office of Prime Minister of the UK.

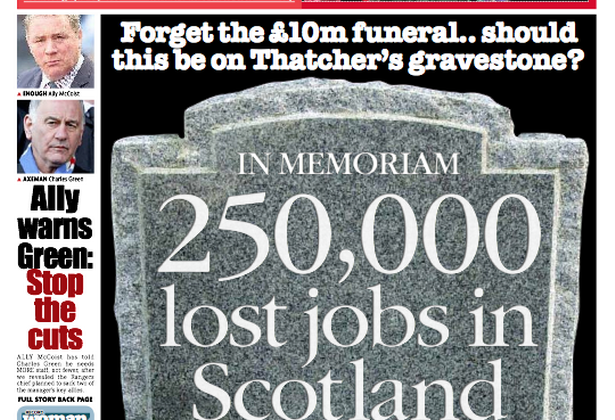

This was, in this case, his remarks celebrating and making light of Thatcher’s closure of numerous coal mines in the 1980s – which resulted in a great big stushie across Scotland and the UK. All of this has generated much heat and expected charge and counter-charge. But we need to think more about why the Thatcher era still matters so much and why.

A few people tried to defend Johnson. Some went down the ridiculous line of ‘Harold Wilson shut more mines than Thatcher’ – right on the numbers, wrong on the politics. And for a large part of Scotland and the UK it was a chance to pile in and condemn the black shadow of Thatcherism which is still cast over so much of our politics.

The bigger question is about the continued fascination, and even hold, which Thatcherism has over us. This is true of the band of true believers holed up in the London right-wing press, think tanks and parts of the Tory Party, but it is also true of its many opponents.

For some the 1980s are the never-ending decade and a defining reference point, with a whole pile of evocative moments and causes – from politically the Falklands War and miner’s strike in the UK to the Cold War and fall of the Berlin Wall internationally to culturally the rise of MTV, outlandish music videos and the emergence post-Live Aid of the ‘charity single’ and stadium rock (cue Dire Straits and U2 as global phenomena).

There is a generational story here, with the likes of some once youthful troublemakers and provocateurs either refusing to stop going on about their moment in the sun (Paul Morley) or becoming bitter, twisted and reactionary (Toby Young, Julie Burchill in an endless list). Thus for these figures the end of the 1970s until the fall of Thatcher provide an equivalence to the way a previous generation used to fixate on the 1930s – mass unemployment, the Jarrow march, fighting fascists and the rise and fall of appeasement of the Nazis by Neville Chamberlain and the Tories.

This is actually about more than Thatcherism but how we see the modern world around us and the epic changes we have all lived through. In the UK the past four decades can sometimes be reduced down to eight words: ‘Margaret Thatcher poll tax Tony Blair Iraq War’. For many on the left, Blair and New Labour were even more than an acceptance of the Thatcher legacy, but an embrace and extension of it. This was seen in the remarks of UCS leader Jimmy Reid – ‘When New Labour came to power, we got a right-wing Conservative government’ – with the implication that even when Scotland voted Labour, along with England the values of Thatcherism remained dominant.

If this is a generational story it is also part folklore, part mythology in the way it is told and retold and also about trying to comprehend and simplify the profound shifts which took place in Western and global politics from the 1980s onward which Thatcherism was only one part of. In reality the Thatcher Government claimed as its own huge shifts in the economy, society and finance capitalism which were already beginning to happen pre-1979, putting Labour on the defensive and making it defend the status quo.

When we talk about Thatcherism now we should be really clear what we mean. In a sense we are trying to summarise the immense changes we have lived through, the transformation of the economy, rise of a more brutal, dehumanising capitalism, the power of finance and the City, and the emergence of a more individualised, less collective society.

Thatcherism, in the period Thatcher was Prime Minister from 1979-90, was never (despite her ideological instincts) a completely coherent intellectual force in how it connected her words and deeds. It was not the transformative, all-encompassing force both its true believers and most passionate opponents think it was and is and in particular how it is portrayed in hindsight.

As Aditya Chakrabortty wrote in The Guardian last week Thatcher and Thatcherism preached lower taxes but entered office with taxes at 30.4% of national wealth and left with them at 30.9% of national wealth, redistributing them from the rich to those on average and lower incomes through the increase in VAT and National Insurance. Similarly she talked of shrinking the state, but never did so with public spending as a percentage of national wealth remaining broadly static but shifting away from the traditional concerns of the post-war social contract and to unemployment benefits and a stronger authoritarian state.

Thatcherism, as defined by the values that Thatcher spoke about when in office, was never actually that popular over the 1980s. What Thatcher and the Tories were able to do is win several elections in a row with what was a clear minority of the vote – 42% – which in previous decades up to 1970 would have seen a party convincingly lose an election. But aided by a divided opposition, defensive Labour Party, Thatcher’s growing sense of her own importance and the statecraft which comes with running UK Government over a period of time, all aided by the supporting chorus from the right-wing press, and it seemed as if Thatcherism could carry all before it.

There is the Scottish dimension in all this. Thatcher was the personification of an abrasive, intolerant English nationalism which cloaked itself in Britishness, but for all it evoking of the union, had little understanding of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. When Thatcher was elected in 1979 the Tories were not that unpopular in Scotland winning 31% of the vote and 22 out of 71 MPs – being the principal opposition to Labour. They lost more than half their seats in 1987 here when they won a UK landslide based on English votes and seats, and after she fell John Major saw the Tories reduced to 17.5% and zero seats. Not only that the SNP replaced the Tories as the main challenger to Labour in votes – thus predicting the shape of politics to come under the Scottish Parliament.

When we talk about Thatcherism we have to be clear about the difference between Thatcher and the ism, and whether we are really describing the past, the present or the limitations of the future. And if we are to finally – 31 years after Thatcher fell as UK Prime Minister – to consign her ism to the dustbin of history we have to stop associating Thatcherism with near superhuman qualities. Rather, we have to start understanding the complex patterns of inequality, wealth and global capitalism, and build a critique of the world we live in and come up with ways of changing it.

If we have to learn anything from the chimera of Thatcherism, we have to have the courage and confidence to think about ideology and values, get serious about statecraft and what you do with the mechanics of government in Scotland and the UK, and critically link this to telling compelling stories of change which help shape the future.

None of this is easy but if the UK is to break out of the wreckage that defines it and Scotland to mark out proactively its own distinctive path, we could all learn from the above. We all need to stop using Thatcherism as an excuse and a catch-all and start creating a post-Thatcherite future.